Abstract

The Snowden revelations have renewed interest in questions surrounding jurisdictional issues about where data is kept (location) and who claims the capacity to direct access to it be given by the entity hosting it (control). While early attitudes to the cluster of technologies marketed as The Cloud generally played down this aspect, and unilateral contracts offered by many major providers declined to specify these parameters for the technical provision of a Cloud service, growing appreciation that assurances of security and confidentiality are no barrier to certain forms of access being granted to third parties in other jurisdictions has rekindled interest. This paper explores the technical and legal issues involved from the perspective of an Australian business interested in both customer and government attitudes, and discusses how moves to implement jurisdiction location and control preferences have been characterised as Data Sovereignty and Digital Protectionism by differing interests.

Contents

1. Introduction

3. Data Sovereignty Risk Management Issues

4. Third party access by legal means: Does it matter where your data is stored, or by whom?

5. A Signals Directorate view of Cloud security

6. Drivers for a Cloud Data Location and Jurisdiction Policy

7. Competing 'Frames': Digital Protectionism

8. Conclusion

1. Introduction

'Then data sovereignty, privacy and security?the importance of trust. ... We conducted a survey [in 2010] of 500 consumers in Australia. ... [T]he number one thing was that Australians were the most extreme in their responses [in] five out of six categories compared to any other country in the world. The only country more extreme about the data was Germany. ...

Australians didn't trust the government with their data: only 20 per cent trusted the government. They trust IT companies [even] less than the government. ...

Australia was the most extreme out of the countries we [surveyed] about keeping data on shore. The data needed to be kept in Australia. So it's not just some rule that APRA's made up or the Privacy Commission's made up. It actually reflects Australian consumers' attitudes to data. They want to keep it here'. (Baty 2011)

What have become known as the Snowden revelations started in June 2013 with stories in the Guardian, ProPublica, Washington Post, later New York Times and Der Spiegel, and more recently the new online vehicle First Look. The scope of the extracts from a cache of tens or hundreds of thousands of files copied from NSA sources by Edward Snowden is remarkable. They purport to reveal an international network of surveillance practices by members of the Anglophone "Five Eyes" intelligence and national security "community" that extend far beyond popular understandings of the controlled and specific powers to tap telephones for law enforcement purposes dramatized by TV's The Wire. Critical attention has focused on what seems to be an omnivorous global dragnet based on warrantless, suspicionless mass surveillance programs with ominous names such as BOUNDLESS INFORMANT, collecting digital metadata and some content data both by the legal means we consider below, and by other technical means that bypass the need for cooperation from the Internet backbones, cloud hosts and telecommunications utilities pressed into service by those legal means.

The revelations have bolstered the need to re-assess issues of 'data sovereignty' in the Cloud (an online service delivery method the technical models for which are set out below). These issues, discussed in this paper, had already been coming to attention in countries around the world, including through scholarly work such as that of Dan Jerker Svantesson (2013) and Christopher Kuner (2010) and attention in EU's Article 29 working party and OECD medical informatics circles, but the frequent absence of concern for the expectations of "non-US persons" in the debates following the exposures have confirmed the need for caution, both in relation to the actual practices revealed, and to the potential for similar hazards in other jurisdictions not similarly exposed, and other business practices in cross-border Cloud services. The time for a more traditional, sober analysis of liabilities, risks and benefits has arrived. The carefree, boundless honeymoon of the Cloud is over.

While the Australian Law Reform Commission and parliamentary committees over the past five years have noted concerns about the Cloud, the mid-2013 developments mean renewed attention in Australia is being directed to issues arising from storage of business and personal data in the Cloud, building on trends already identified in the industry insider Baty's view quoted above, coming to us from a more innocent, pre-Snowden era. We investigated questions such as the following:

- How can Cloud services be used safely, and when can they be dangerous?

- What is 'data sovereignty' in the Cloud? Does anyone know or care about legal jurisdiction over data in the Cloud, or is 'cyberspace' somehow beyond such administrivia, as customers are implicitly invited to imagine by some Cloud proponents?

- What happens if you ignore data sovereignty in the Cloud? Does it really matter where data is stored, or by whom?

- Will you be able to rely on Cloud data stores when you need them? Will you be able to protect them against unwelcome adverse access or retrieval by parties other than the data owner and their authorised agents?

- In a court case, could you prove and exercise your/the owner's rights to control, access or delete data held in the Cloud?

The Australian Communications and Media Authority chair explains data sovereignty as "the ownership of data and access to data stored in countries, other than the one where the end user resides, including relevant redress mechanisms and the capacity of citizens of Australia to take action or seek redress against cloud providers in other jurisdictions" (Chapman 2013).

Many organisations' document or data management policies may not yet adequately cover data jurisdiction, the key issues of where it is located and who has the capacity to control it, nor recognise challenges thrown up by a somewhat chaotic, rapidly-evolving cloud services environment increasingly integrated with 'Big Data' capacities (Mayer-Schonberger & Cukier 2013).

Governments and regulators seeking to "drive confidence among businesses and users that cloud service contracts will be designed with relevant risks and benefits that have been appropriately weighted and addressed?'balanced' (Chapman 2013) ? may also have to pay more attention to the 'risk' side of the equation in this jurisdictional area. A feature of many Australian Cloud policy and strategy documents[1] appears to be an almost boosterish urge to encourage and foster Cloud take-up for its own sake (no doubt welcome to the ears of cloud providers): identifying the benefits, but tending to leaving the hazards, especially those related to jurisdiction, un-named or relegated to a footnote (DBCDE 2013; AGIMO 2013). Confidence may be better served by a more detached, fine-grained risk/benefit assessment of the match between your own data's sensitivity and needs, and the willingness and capacity of Cloud services to deliver reliably, including the potential effects of where they are located and by whom controlled, and the regulatory regimes that become important when things go wrong.

This paper looks at issues affecting data sovereignty in the cloud, and their implications for managing the potential risks and rewards of handling new cloud services safely. The focus is the Australian jurisdiction, but the principles in government policies, standards, case law and even legislation are increasingly being reflected in different jurisdictions around the world. Some countries play a more central role in the cloud industry than others; we offer international equivalents and comparisons to put the differences and similarities in context.

How do cloud legal issues in relation to jurisdiction or location differ from those arising from conventional outsourcing or hosting?

It is easy to exaggerate the difference a Cloud makes. In many ways, the issues start from the same foundation. Traditional hosting or server hire contracts involve use of someone else's storage or computers. "But it would normally have been clear who you were dealing with and where your rented resources were. Such arrangements were also unlikely to have been established on a casual or informal basis. With cloud computing, however, the location(s) of your data [and under whose jurisdiction they fall] may be unclear, possibly even unidentifiable and it is also much easier to set up such an arrangement. The ease with which cloud resources can be allocated and reallocated makes it more likely that it will be done without an appropriate review of the relevant legal issues." (QMUL 2010)

Why are cloud sovereignty and data jurisdiction important?

Most documents are now digital and networked

Once removed from the physical constraints of hard copy, networked digital documents can be copied and moved between locations or jurisdictions with trivial effort.

Foreign litigants and governments have a much easier time getting access to your data if it is within their jurisdiction

While there are international or inter-country arrangements which enable access in or from other countries, most countries favour access requests made in relation to local documents, or documents under the control of entities over whom they have jurisdiction.

Laws in other countries may be quite different from those in your own country.

Third party legal access options, including detailed comparisons of mechanisms for such access under Australian jurisdiction and under that of the main cloud hosting forum, the US, are complex, so we discuss some examples in section 4 below.

Cloud data storage contracts may be on terms unfavourable to users, or silent on key issues

Particularly for Web-grade IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service; see below for cloud acronyms), service provider business models may rely on excluding liability for matters which may be within their control. Typical SaaS (Software as a Service) host models may also depend escaping liability for such matters.

Some countries or jurisdictions may have worse IT, security or privacy protections for your data than Australia; or their protections may be harder for local subjects or owners to use

The evolution of business, legal and technical support for adequate online security, confidentiality, privacy and/or data protection vary greatly from country to country. International agreements such as the Convention on Cybercrime from the Council of Europe (CETS 185, in force in Australia from March 2013) arose to address this in some areas, although recent developments in aggressive surveillance and associated moves by agencies to undermine cryptographic standards have suggested that it may have paradoxical effects in others, potentially reducing security and confidentiality against the intervention of foreign agencies. Many countries (although probably the minority of major cloud participants) are not a party to relevant agreements; some of them also have quite underdeveloped legal coverage of online issues generally, and may not support a robust confidentiality and privacy regime.

And those who are parties to a Convention may have varying implementations of its model laws, and differences of focus between enforcement and confidentiality. The US and Italy for instance have exposed their citizens to fewer of the more extreme effects of the Convention than has Australia, meaning that rights and obligations may not be symmetrical (differing attitudes to strictness of requirements for dual criminality, or to weakening the need to prove a mental element in certain cybercrime offences are examples).

Practical IT security implementations, or the degree of protection of Australian-owned data from third party access, will vary according to these and other local factors. This is a major feature of the paper.

Increased scrutiny and professional liability

Inability to either produce data in response to legal request, or to protect it from unwanted demands from third parties, may create a significant governance impact. Such an outcome, in the worst case, may mean not only is the future of the organisation at risk, but also the personal reputations (or even the civil or criminal liability) of those directors or executives who lead it.

Strategic importance to the organisation: methodical solutions needed

The judicial gaze has begun to focus upon the entire stores of information held by companies, and how companies deal with, and secure or fail to secure, those stores. Governments increasingly require transparency around IT security failures (data breach notification); a version of the 2013 Privacy Alerts bill to amend the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) to make such notification mandatory, consistent with expectations in many US and EU jurisdictions, may yet be reintroduced. And every Internet user has been alerted, by the media at least, to the risk of their data being subject to access by unwanted parties (albeit at some risk of 'data breach fatigue' if they are not given practical response options).

Corporations that do not have in place strategic, comprehensive and reasonable data storage, location and jurisdiction policies, methodically and consistently adhered to in implementation, chance a fate serious in its potentially destructive outcomes, if the ire of judicial, regulator or market condemnation falls upon them. While many escape serious consequences (Telstra's recurrent large scale breaches come to mind), the risk of such condemnation remains.

What is cloud data?

Companies and individuals generate a plethora of digital documents, all of which are now candidates for, or generated by, cloud storage. For example:

- Images and recordings from mobile or other devices

- Imaged versions of original paper documents

- Files (including word processing, spreadsheets, presentations)

- Email (including email messages, instant messages, logs and data stores)

- Databases (including records, indices, logs and files)

- Logs (including accesses to a network, application or Web server, customer tracking or profiling)

- Transaction records (including financial records)

- Other forms of meta-data

- Web pages (whether static or dynamically constituted)

- Traditional audio and video recordings and streams

- App data sets

- Software itself may constitute a significant cloud data holding

- Access control information and passwords

2. Types of Cloud Services

Different cloud models implement varied technical and processing attributes, and raise a range of different legal and policy issues around data sovereignty.

Cloud Service Models

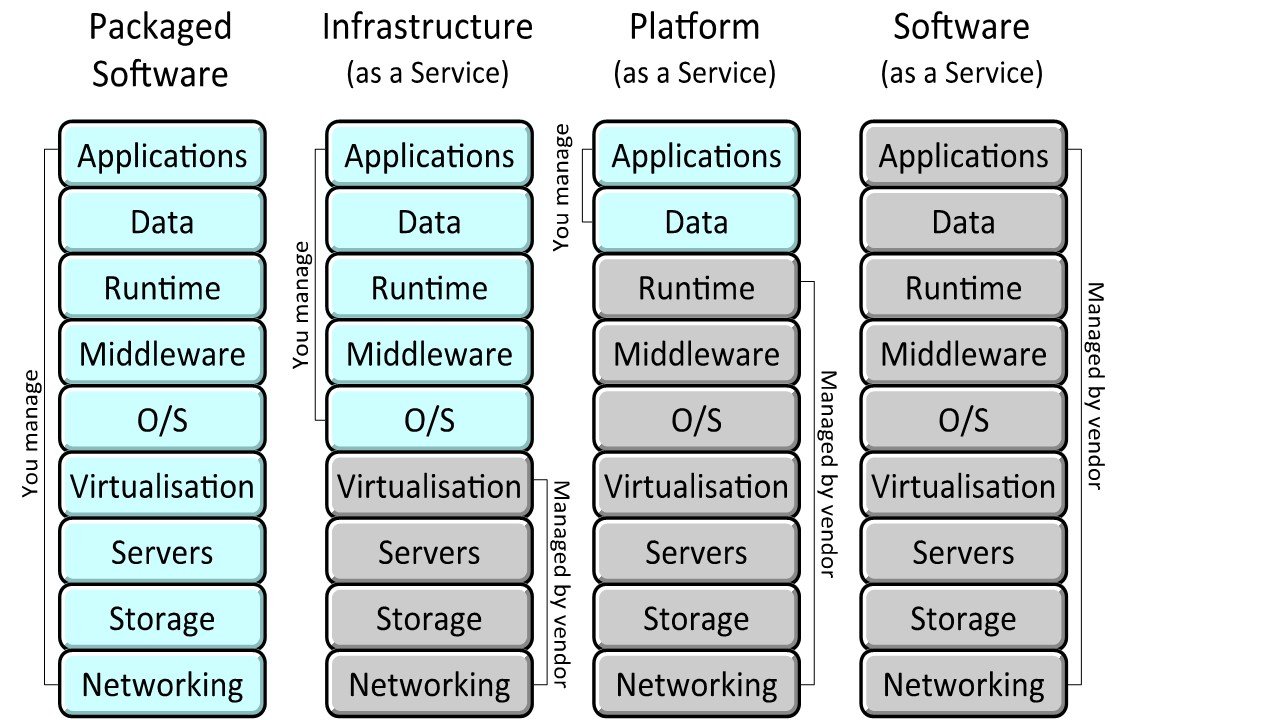

Cloud computing services come in three main "Service Models", which vary according to the extent of the stack managed by the vendor compared with that under the control of the customer, and thus the level of interaction between the cloud service and the data it is holding.

Figure 1. Cloud Service Models (Ludwig 2011, after Microsoft) [2]

Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS)

Here the relationship and interaction between the cloud service and the data may be small or minimal. With "Infrastructure as a Service", the service is limited to the provision of the infrastructure needed.

Platform as a Service (PaaS)

Interaction is medium when the cloud provider furnishes hosting and a platform, but not the specific applications running on it. This model is known as "Platform as a Service."(Gilbert 2010)

Software as a Service (SaaS)

The interaction may be large or frequent in "Software as a Service." The SaaS customer has access to a wide range of capabilities; the cloud provider furnishes hosting, storage, platform, as well as software applications for immediate use with the customer's data. Many consumer Cloud offerings like FaceBook, Google Docs, Apple iCloud or Microsoft OneDrive include core SaaS features.

Other Service Models?

Some commentators (Gilbert 2010) suggested other Cloud Service Models but the ones set out above appear to be a useful core set for most purposes.

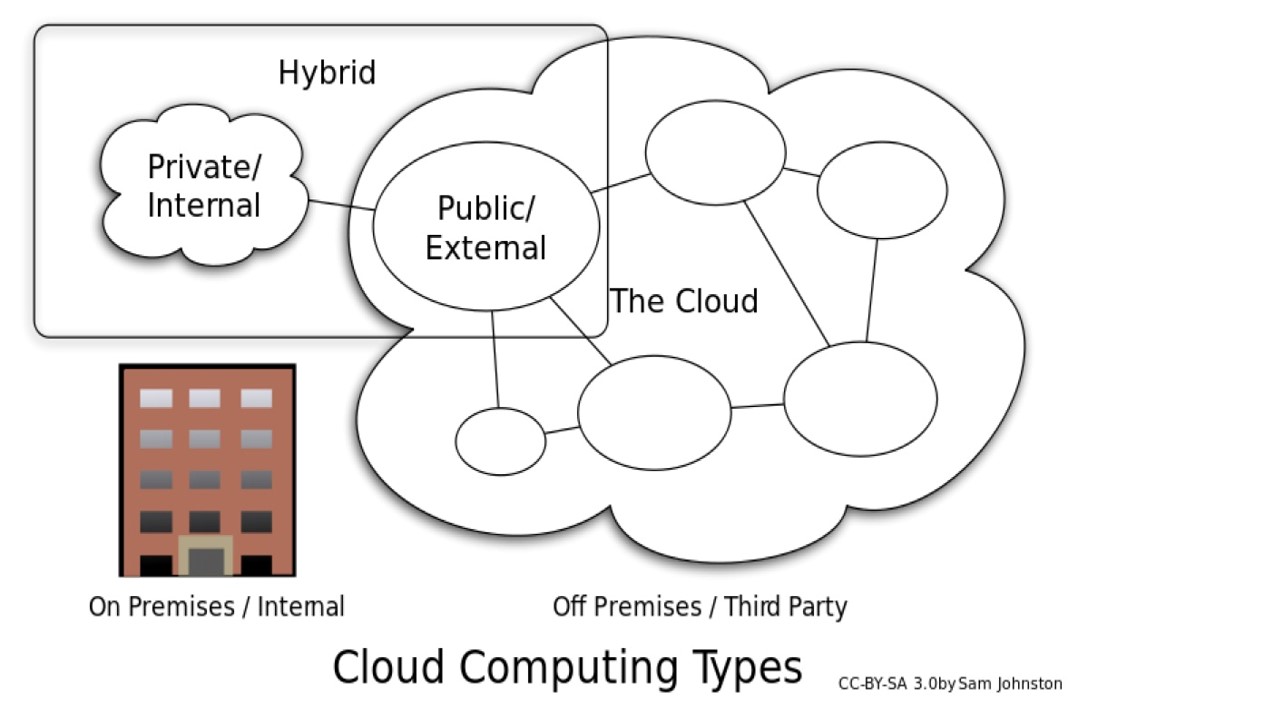

Cloud Delivery Models

Cloud computing capabilities can be implemented and used in four main "Delivery models": Public, Private, Hybrid, and Community. The choice of delivery model has significant effect on the nature, content, and terms of the Cloud contract, and associated risks.

Public Cloud

The public cloud infrastructure is made available to the public, or a large industry group, and is owned by an entity selling cloud services. It is potentially the lowest cost model, especially if at the 'Web-grade' rather than 'Enterprise Grade' end of the assurance spectrum. This is more accessible to small entities, but the terms and negotiability of the contract usually offer limited comfort. Most Amazon Web Services fall into this category, as do many offerings from Google, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft.

Private Cloud

The private cloud infrastructure is operated solely for an entity. It may be managed by the entity or a third party, and may exist on-premises (presumably avoiding sovereignty or jurisdiction issues) or off-premises (which could be anywhere). It is more attractive to larger entities and government because of their greater capacity to manage their part of the investment and support required.[3] Many of these are not publicly visible, because they do not need to be.

Hybrid Cloud

The hybrid cloud infrastructure combines private, community, or public Clouds that remain unique entities, but are bound together by standardized or proprietary technology that enable data and application portability, such as when cloud bursting for load-balancing between clouds. Many of the public cloud providers also offer private options, and can integrate the two. Data of different categories or sensitivity may thus be hosted in different delivery models, or indeed in different locations or under the control of different entities.

Figure 2 ? Types of Cloud Computing [4]

Community Cloud

This approach is less common, typically used by government. A community cloud infrastructure is shared by several entities, supporting a community that has shared concerns, such as the same mission or policies, or similar security requirements or compliance considerations. It may be managed by the entities or a third party, and may exist on or off premises. (Gilbert 2010) Many government cloud installations are candidates for such a model.

Some features and risk attributes are shared by all Cloud models, while others are more applicable to particular models. We only refer to a particular model if it is relevant for a particular risk or feature. Often by default it will be public Cloud delivery model, although off premises private clouds.

Real world: A mix of models and risks

The issues under consideration when we look at an actual Cloud implementation instance will vary depending on the service, the business, and the data held by the service. Most customers in reality use a combination of cloud service models depending on the type of service needed, the utility of the service offering, and the risk of the data.

- For example, in an Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) arrangement, the service provider would not be expected to have any access to data at all.

- Some service providers also provide SaaS where all data is encrypted from the customer's desktop: this means data is not accessible by the service provider either.

This question of who can see the data, and on what basis, is important to the overall risk of putting data in the cloud, and should be a focus of analysis. Service and Delivery Models are a useful framework for this, but it is critical to understand the details of data access, and weigh up the actual risks of a particular Cloud implementation.

A related issue is important for discussions about access to data by regulators (including those discussed in the Third Party Access section below): as a practical matter, law enforcement is unlikely to know that a particular company has data in one of the many cloud services operating in a jurisdiction, under whatever Model, so the best way to get data from a company may be to just directly order that the company deliver it up!

Where the data is stored or hosted in a jurisdiction but the legal entity is absent from it, the risk that the cloud data will be located and accessed by law enforcement may be higher or lower than if they were present, depending on configuration, contract and control details. (However, if the revelations in the documents leaked by whistleblower Edward Snowden are accurate, this risk is probably often higher than earlier appreciated, given the apparently omnivorous appetite for metadata surveillance by members of the 5 Eyes group, and possibly others.)

It is also useful to give close attention to the characteristics of the data, and the risks that different categories of data carry: only some classes of data are actually dangerous if lost. There is of course typically the embarrassment of a data breach: note the recent finding by ACMA against AAPT (ACMA 2013), the new penalties, and actual and proposed new disclosure obligations in the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth)[5].

But it is also important to ask, how often is money or valuable data actually lost? The Verizon Data Breach Report (Verizon 2013) has examples with detail of the types of breaches and the proportion where the information lost actually could cause loss. The incidence of loss, and the security response appropriate, will vary from case to case. (The Privacy Amendment (Privacy Alerts) Bill 2013,[6] the disclosures starting June 2013 (Greenwald 2013; Gellman and Poitras: 2013) and still continuing regarding secret NSA, GCHQ and related surveillance programs for data mining telecom and Internet providers, and the Australian National Cloud Computing Strategy (DBCDE: 2013)[7] combine to elevate cloud computing to the top of risk management considerations.)

Having outlined the Models by which Cloud services can be categorised, and considered some of the real world complications which show that the devil is in the detail rather than the model, we turn now to the question of the exposure of data to third party access in the main Cloud hosting jurisdiction, the US.

3. Data Sovereignty Risk Management Issues

There are many practical reasons a company or agency might be cautious about having its data transmitted beyond its own national borders, or held by entities under another jurisdiction's supervision.

Offshore data centres in distant locations are obviously more difficult to monitor than local ones. Moreover, some parts of the world are simply more vulnerable to natural disasters, wars, so-called "acts of God," or government intrusions.[8] Chief among the multitude of concerns about cloud computing is the fear that a business could have its data transferred to or into the control of an undesirable jurisdiction, without its knowledge or approval, and become subject to unacceptable exposures and legal obligations.

The concept of "data sovereignty", introduced above, refers to both specific data sovereignty laws limiting cross-border data transfer, as well as the more general difficulty of complying with foreign legal requirements that may be more onerous, less clear, unknown to the user, or even in conflict with the user's own country's laws. If the server location or control is not disclosed by the cloud provider or if it is subject to change without notice, the information is more vulnerable to the risk of being compromised. Uncertainty on this point is a risk factor in itself.

In addition, some nations' data sovereignty laws require companies to keep certain types of data within the country of origin, or place significant restrictions on transmission outside the country of origin. Some jurisdictions' privacy laws limit the disclosure of personal information to third parties, which would mean that companies doing business in those countries might be prohibited from transferring data to a third-party cloud provider for processing or storage. (It is worth noting the proposed secret TransPacific Partnership agreement reportedly appears to feature a specific provision prohibiting participants, such as Australia, from enshrining data location restrictions, and the equivalent Atlantic proposal includes similar constraints on domestic law. On the other hand the Article 29 Working Party has suggested that the EU consider restrictions; and they have been mooted by EU ministers and data protection commissioners post-Snowden.)

Information stored in a cloud environment can conceivably be subject to more than one nation's laws. Indeed, the legal protections applicable to a single piece of data might change from one moment to the next, as data is transferred across national borders, or to the control of a different entity. Depending on where the data is being hosted or by whom it is controlled, different legal obligations regarding privacy, data security, and breach notification may apply.

Where there is a lack of specificity, a business will often feel compelled to err on the side of caution and adhere to the most restrictive interpretation. (Others may assume that 'industry practice' will suffice, and the OAIC APP Guidelines[9] of March 2014 tacitly accept a less restrictive approach. However ACMA's history of penalties suggests caution has a place.)

In some circumstances, this may mean that large categories of data should not be allowed to be transmitted beyond the country's geographic borders, or outside its jurisdiction. As a result, some businesses are employing a hybrid cloud strategy which involves contracting with multiple cloud providers that maintain local data centres and comply with the separate, local legal requirements for each country.

The complexity of these various data sovereignty laws may make businesses reluctant to move to a cloud ? especially a Public cloud, as described above ? where it cannot restrict the geographic location or jurisdictional control of its data, and where the characteristics of data warrant such caution.

In concept, using a public cloud on a multinational scale should be highly flexible and cost-effective for a business. One of the attractions is the promise of effectively outsourcing a range of costs and risks. However, t data sovereignty restrictions to which a company may need to adhere in relation to some of those risks can create a daunting challenge.

Despite the notable benefits, many companies can be reluctant to utilize cloud technology because of fears regarding their inability to maintain sovereignty over the data for which they bear significant legal responsibility. (See also sections below on obligations and third party access.)

The Australian Experience

The new Australian Privacy Principles created by the November 2012 amendments to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth), appear to significantly change the test for personal data transferred out of Australia.

- The prior Principles required "reasonable efforts to ensure comparable security," which is difficult to qualify or quantify.

- The new Principles require the outsourced third party service provider "comply with Australian law," and there is greater expectation that the details of foreign jurisdictions in which personal data is hosted be disclosed

While there remains in the APP Guidelines (OAIC 2014) an emphasis on reasonableness, the new standard is potentially tighter, and the disclosure of diverse foreign locations hosting personal information of Australians potentially impacts reputation[10]. Thus, there may be an incentive to consider hosting in-country, or under a regime that is known to be even more rigorous and safe in practice than Australia's. In January 2013 it was announced that CERT Australia would soon be part of a new Australian Cyber Security Centre, which aims to develop a comprehensive understanding of cyber threats facing the nation and improve the effectiveness of protection, which have raise the bar for expectations of effective security in Australia (although it is too early to tell if this will eventuate, given the potential effect of other developments in the Snowden material raising questions about official involvement in moves to undermine security).

The use of cloud technology in Australia is in flux, as regulators hurry to keep up with the evolving technology and increasing popularity of cloud solutions. Moreover, Australia's information security law is comprised of a bewildering amalgam of federal, state and territory laws, administrative arrangements, judicial decisions, and industry codes, (Connolly and Vaile: 2012)[11] so evaluating the impact of cloud sovereignty issues in this context becomes difficult. Changes are due in 2014[12].)

Nevertheless, cloud computing is definitely on the rise in Australia. A recent study reported that more than half of the subset of Australian companies examined spend at least ten per cent of their IT budgets on cloud services, and 31% of companies spend over 20% of their budget on cloud solutions (Frost and Sullivan 2012).

Australian banks and insurance companies are regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), and are required to consult with APRA in connection with outsourcing computing services offshore. Other Australian businesses are required to comply with the Privacy Act and the Australian Privacy Principles, which prohibit the transfer of personal information to a third party outside Australia unless that country has equivalent laws or the entity takes reasonable steps to ensure that the overseas recipient does not breach the APPs in relation to the information for the data (OAIC 2014, Chapter 8) [13]. Many state and territory privacy laws contain similar expectations.

The regulating bodies of some Australian industries, such as banks and insurance companies, may, as a practical matter, require that data be hosted exclusively within Australia. (APRA 2010)[14]

Organizations in Australia, such as defence bodies, education providers, and healthcare organisations, may be required to adhere to the requirements of the Australian Government Information Management Office (AGIMO) to the extent they are directly acting for federal agencies. AGIMO has set out issues to be considered by agencies that are exploring cloud services (AGIMO 2011) [15]. These agencies generally prefer to use data centres within Australia in order to maintain physical jurisdiction over their most sensitive data. (Many other activities of organisations other than federal agencies may not be required to adhere to AGIMO's guidance, depending on the nature of the contracts involved and of the organisation.)

Some cloud providers in Australia will commit to host services within national boundaries to alleviate these data sovereignty concerns. However, even if the data itself is hosted domestically, it is nonetheless conceivable that some service providing access to the data (for instance, in the case of certain models for offshoring by banks) could be hosted in a foreign jurisdiction, or under the control of another jurisdiction.

The Potential Impact of Foreign Regulatory Requirements

Australian companies considering cloud services should consider legal developments abroad when assessing the relative risks and benefits.

Cloud hosting on a global scale is often based in data centres in places like the US, central Europe or Singapore which offer cost and other benefits. It may often store data connected to EU as well and Australian citizens. Differences between the regulatory frameworks where data is hosted, where hosting companies are based, and where data subjects or data users are based can create complex compliance environments. Some aspects can present a legal risk that cannot be fully offset by contracts or technology alone. (Irion 2012) (See also the Third Party Access section below.)

European Union

The European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA) launched a report in February 2013 taking a 'Critical Information Infrastructure Protection' approach to cloud computing, which calls for better transparency regarding logical and physical dependencies, such as which critical operators or services depend on which cloud computing services (Dekker 2012) [16] .

The European Commission is also considering new data protection requirements that would effectively apply throughout the world, including in Australia, to companies active in the EU market or which host data about EU citizens (EC Directorate-General for Justice 2012) [17] . If these proposals are implemented (Neilsen 2013), cloud providers with EU customers would be required to adhere to such legal obligations for all of their data holdings, including data hosted for Australian customers.

European laws impose some limits on cross-border data transfers. The existing European Data Protection Directive obligates entities to maintain the security of certain categories of personal data, and permits the transfer of such information outside of the EU only to those countries the EU considers to have satisfactory data protection laws or if the company to which the data is transmitted agrees to comply with EU law (Directive 95/46/EC ). As a result, data may not simply be transferred at all to a cloud provider with servers located in countries whose data protection laws do not satisfy EU standards.

US regulators, pointing to increasingly robust proposals for increased regulation domestically, have recently suggested that emerging approaches to data protection in the US are more consistent with the EU approach than is widely appreciated, despite PATRIOT Act access and other emerging issues (Robinson 2013). (EU regulators and politicians appear to remain unmoved, with initiatives in the opposite direction in relation to 'Safe Harbor'.)

EU laws on 'discovery' for litigation purposes, and on national security, may be inconsistent with US laws such as the USA Patriot Act in some circumstances (Forsheit 2010). This may lead to confusion or conflict over appropriate responses to requests for access for this purpose.

USA

The United States has no overarching nationwide data protection law (HIPAA, though national, is restricted to the health sector), but it does regulate disclosure of certain categories of personal information to third parties through a variety of laws[18]. The US government asserts extraterritorial claims on data that potentially affect non-US entities through the USA PATRIOT Act [19]. These are discussed further in the next section.

Even companies which try to require their cloud providers to keep their data within the geographic borders of their own country cannot assume that they are subject only to their home country's laws because, in certain circumstances, cloud providers may be legally obliged to communicate information, including personal information, to authorities [20] .

For instance, if a company is based in a country which prohibits disclosure of personal information without the subject's consent, it could conceivably violate its own nation's laws if it complies with a demand by the US FBI to turn over information stored in a US company's cloud, or in a cloud data store located within US boundaries. (See the SWIFT case below for an example on this point.)

There has efforts made to deal with these troublesome issues. The US Department of Commerce and the European Commission jointly developed a "Safe Harbor" to streamline the process for companies to comply with the EU's Data Directive[21]. Intended for EU and US companies which store data, the Safe Harbor is available for companies which adhere to the seven privacy principles outlined in the EU Directive. A similar Safe Harbor framework exists between the US and Switzerland[22], among others.

Of particular concern to cloud computing customers are the requirements that data subjects be informed of data transfers to third parties, and be provided the opportunity to opt out. (The 2012 proposals for EU data protection, above, include increased emphasis on effective consent rights for data subjects, so this may continue to be relevant when and if these proposals come into effect in 2014 or later.

There have also been mounting criticisms of the effectiveness of Safe Harbor from a compliance perspective, including by UNSW research associate Chris Connolly. (Connolly 2008) These recently bore fruit in a review of trust schemes associated with it. (FTC 2014)

Data may also only be transmitted under the scheme to third parties who follow adequate data protection principles, thus obligating the cloud customer to ensure that its cloud provider operates responsively. Clearly there have been doubts about the effectiveness of this scheme; the Article 29 Working Party highlighted the question of whether individual/corporate consumers are in a position to understand (ie to give meaningful consent) and enforce such obligations.

More recently, EU concerns about the late 2013 revelations by Edward Snowden have brought the Safe Harbor model into question, given the apparently limited or non-existent constraints it has placed on warrantless suspicionless mass surveillance of non-US citizens. (Rodrigues et al 2013)

The European Parliament, after it adopted the text of the proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation on 12 March 2014, also went so far as to pass a resolution setting forth its findings and recommendations regarding the National Security Agency surveillance program. Among other things, the resolution calls for:

- withholding the Parliament's consent to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership if European data protection principles are not fully respected;

- suspending the Terrorist Finance Tracking Program until alleged breaches of the underlying data disclosure agreements have been fully clarified; and

- suspending the Safe Harbor Framework immediately, alleging it does not adequately protect European citizens. (Hunton & Williams 2014)

The long term future of the Safe Harbor scheme is thus unclear.

Canada

Canada presents a complex situation, as its data protection legal landscape is a patchwork of federal, territory, and provincial laws. It has laws requiring that certain data stay not just within Canada, but within specific territories and provinces[23]. Of particular interest is Canada's assertion that its privacy laws apply beyond its borders. The Federal Court of Canada held that the PIPEDA law gives the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) the right to investigate complaints relating to the flow of personal information outside Canada, regardless of whether the company involved is Canadian[24] . If personal information about Canadian citizens is involved, the country's privacy laws and the OPC's investigatory powers extend across borders to foreign-based companies, though there are of course the sovereignty dilemmas around giving force to such powers.

No uniform standards

Many other countries have proposed or are in the process of developing new laws regulating data privacy and related matters, and there is little hope of a uniform, worldwide standard which companies could confidently follow to ensure compliance.

Data breach notification laws, for instance, vary greatly from one jurisdiction to the next. (Maurushat 2009) Some companies resolve this concern by storing only public data on public clouds, and keeping confidential information within their own control. Nevertheless, even where the data remains within the geographic borders of Australia, it is possible that the cloud provider entity is subject to the laws of another country.

In addition, data which is transferred outside Australia to one or more countries may become subject to a variety of external laws. Business organizations which operate across borders face unique challenges in managing network security risk, and those which use cloud computing technology have even more complicated exposures. A recent Capgemini study revealed that management considers "issues with data sovereignty" to be the second most important factor ? just after "fear of security breaches", and before the raft of technical and management issues ? in determining whether to adopt a cloud infrastructure (Capgemini 2012).

Therefore, along with concerns about integration and business agility, businesses are starting to realize the serious and complex issues involving data sovereignty in the cloud computing context.

4. Third party access by legal means: Does it matter where your data is stored, or by whom?

This chapter drills into a core question: the complex of factors and legal issues which influence whether third parties can assert their right to access your data hosted in either a local cloud (in Australian jurisdiction) or in an offshore cloud (typically through services based in the US, the main cloud hosting jurisdiction).

Its observations may help guide your assessment of whether these jurisdictional issues warrant consideration of a 'data sovereignty'-aware cloud policy.

Introduction

For some time, improved global networks and the Internet have enabled hosting service providers to store data in low-cost jurisdictions, or where close proximity to large markets and scale facilities can create economies of scale.

In deciding whether to host data overseas, prudent customers have typically considered the cost of the service, security, and the sovereign risk of the location.

After an initial rush of cyber-libertarian optimism, the wishful thinking of the early 1990s in which 'cyberspace' was somehow beyond the bounds of earthly law, there is a sobering recognition that information is still subject to the laws of the jurisdictions where it is held, or which regulate entities who control or host it.

Data hosting customers need clarity about whether remote hosting will involve transferring data to a foreign legal environment that may bring new risks or create special concerns. In particular:

- does the service provider ensure that the foreign host provides a service that complies with Australian standards for privacy and security?

- what are the implications of exposing data held offshore, or under the control of offshore entities, to examination by foreign law enforcement regimes or litigants?

Government data users in particular feel the pressure of these questions.

Such concerns may be exacerbated by the ability and practice of certain law enforcement agencies to inhibit or prevent owners of the data from knowing that their data has been accessed and is subject to examination.

Focus on these issues has intensified with the advent of "cloud" computing. Information held "in the cloud" may be stored in multiple locations, and in multiple jurisdictions. Cloud computing with global networks obscures the customer's knowledge and control of the regulatory risk associated with the jurisdiction/s where the data is held, or by whom it is held.

Where the customer is itself storing and managing the information of third parties, this lack of information represents a failure to achieve transparency. For many customers a failure to fully understand the issues and risks associated with potential foreign access to data held in a global cloud may be illegal.

Many of the commercially available cloud computing services are offered by US-based companies at present, so in this paper we consider the potential scenarios under which a US-based data hosting service provider may be compelled to provide access to stored data to third parties, such as US government authorities and private litigants. We also comment on comparable laws in Australia, and issues raised in relation to European countries.

(While this paper does touch on both US and Australian law and practice, it is not intended as an abstract comparison of the substantive laws of the two countries; this would be a somewhat misleading basis for an Australian company considering relevant business and regulatory risks in the choice between hosting data under Australian jurisdiction or under other those of typical commercial cloud services. We offer a few comparisons with certain Australian provisions as a context for this risk analysis. However, even if local and cloud storage jurisdiction laws were identical, other practical factors are more burdensome dealing with third party claims to access an offshore data store. For instance the costs of legal action, enforceability of remedies, and investigation or monitoring of developments are all more problematic in another jurisdiction since a local entity will often not have any presence there. These are of course to be offset against the hoped-for benefits of Cloud scale services.)

Background

As a practical threshold item, we note that the US government is usually interested only in matters that concern US interests, for example, payment of US taxes, crimes in violation of US laws and threats to US national security. Much of the information held in cloud stores under US jurisdiction on behalf of foreign data owners may be of little interest to them for this reason. But from the examples we consider in this summary, it is apparent that US authorities will not apply particular self-restraint in scenarios involving foreign jurisdictions and US interests.

Compliance obligations under foreign laws on US companies (or their foreign data sources) not to provide data to the US government are not recognized as a defence to information requests by US courts or authorities. Additionally, as many data owners would be aware, US authorities can in most cases also obtain data under international cooperation treaties through foreign governments (as can Australian authorities).

Different Types of Data Requests

Informal requests

US government agencies typically have investigative duties and authority under the statutes or regulations of their establishment. As a result, government agencies can approach individuals and companies (including data hosting service providers) with informal information requests. Many US companies are willing to comply with such requests, to cooperate with the US government on issues of shared interests (e.g., fraud prevention on e-commerce websites) or to avoid contributory liability for illegal activities (e.g., copyright infringement).

Some companies are also obligated to comply with certain information requests. For instance, financial service providers have to cooperate with certain regulatory agencies and provide certain records as a matter of statute, and telecommunication service providers have to provide access for law enforcement purposes under CALEA. (BeVier 1999; Kisswani 2012)

But, in the absence of such specific regulatory compliance obligations, individuals and companies do not have to answer to informal information requests from US government authorities.

Summons and subpoenas etc.

Most US government authorities are entitled under specific statutes to issue formal information requests ? summons, subpoenas or other forms ? which either have to meet certain minimum conditions (e.g., IRS summons) or which are generally permissible so long as there is some relevance of the inquiry to the mandate of the requesting authority and the subpoena does not violate constitutional or statutory limits. For example, grand jury subpoenas issued by US attorneys are generally legal and compelling unless they violate the US Constitution or certain limiting statutes. Grand jury subpoenas also contain secrecy restrictions to protect the grand jury process from inappropriate influences.

The applicable limitations in the US Constitution and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) are discussed below in more detail, but for purposes of this summary it is important to note that information requests in the form of subpoenas are generally compelling, unless an exception applies. If an exception applies, the recipient of the subpoena can assert it and demand that the government narrow the scope of the subpoena or withdraw it.

In situations where subpoenas are not available due to statutory limitations, US authorities can be authorized to obtain a formal warrant, which has traditionally required a court order, probable cause and other conditions to be met, and is therefore more difficult to obtain for US authorities. But recent legislation and government practices are believed to have weakened the protections previously afforded by warrant requirements, as further discussed in this article.

Digital Due Process Coalition and demands to limit access

A number of US-based data hosting service providers and other organizations, including Google Inc., Microsoft Corporation, AT&T, and eBay formed the Digital Due Process Coalition[25], which asserts that technological advances have outpaced the ECPA, and thus "the vast amount of personal information generated by today's digital communication services may no longer be adequately protected." This organization and various privacy activist groups demand that access to personal data (hosted by data hosting service providers and other companies) by US government authorities be limited. Demands include that the situations where US government authorities need warrants be expanded, that warrants should not be ? or be less often ? available without court orders, that additional limitations should be imposed to legitimize subpoenas (e.g., by enacting new statutory restrictions or interpreting the US constitution to protect privacy interests), that electronic documents stored in the "cloud" be afforded the same Fourth Amendment privacy protections as electronic documents stored in traditional formats, and that consistent standards be set forth for government access to electronically stored information.

Unless and until such reforms pass, the investigative powers of the US government are limited primarily by the following constitutional principles and laws.

Australian Comparison

There is no similar industry lobbying to tighten privacy laws in this way in Australia, nor coordination with local privacy advocates. The previous Australian government was pursuing a policy of compulsory general data retention by carriers and service providers with a view to making archived information available to law enforcement authorities; this would add to recent changes obliging ISPs to retain certain traffic data on specific request. This policy was consistent with perceived obligations under the Council of Europe Cybercrime Convention. It was opposed by industry, but returned to active consideration as the 2012 'Data Retention' proposals.

The Australian Privacy Act 1988 does not prevent a local company from providing personal information to regulatory authorities without legal compulsion if this is disclosed in the Privacy Policy of the company. Some Privacy Policies state that personal information will not be disclosed to regulatory authorities or other third parties without legal compulsion. The concept of 'implied consent' has been used to justify provision where such statements are more ambiguous.

There are currently few Australian statutory restrictions or conditions on the offshore transfer of data which may become subject to such access. Contractual protections are also of limited value in the circumstances discussed above, especially to data subjects.

Privacy law reform for transferors to generally "remain responsible" after offshore transfer may be of limited benefit[26] to local data owners or individuals once personal data is disclosed as a result of foreign government or litigant compulsion or effective request. (Barwick 2012a)

There has, not surprisingly, been interest in whether more restrictive oversight of transfer of personal data overseas will be needed in order to bolster the responsibility of transferors. For instance, Senator Stephen Fielding (an independent, though with potential balance of power in the Senate at the time) introduced the Keeping Jobs from Going Offshore (Protection of Personal Information) Bill in 2009, which would have required companies to gain customers' written consent before their personal information could be transferred offshore.

The 2012 amendments to the Privacy Act now in force, while not requiring explicit consent, appear more likely under APP 8.1 and s 16C to impose liability on Australian hosts for data breaches which occur offshore in some circumstances. (See also the Privacy Alerts bill 2013, which would have imposed reporting obligations.)

Limitations on Searches and Seizures under the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution

Generally, the primary limit on the US government's power to obtain personal information is the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution, which prohibits "unreasonable searches and seizures." Under the Fourth Amendment, the government must obtain a warrant supported by probable cause that a crime has been committed, that describes the "place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized," and provides simultaneous notice of the search to the person. Whether a search and seizure is "reasonable" depends on whether the person has an objective "reasonable expectation of privacy" in the item subject to the search (Cate 2007).

The protection afforded by the Fourth Amendment, however, is not absolute, and there are many exceptions to the warrant requirement.

One such exception is for data held by a third party. Under this "Third Party Exception," a person does not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in information he or she discloses to a third party. For example, the government does not need a warrant to seize documents that a person conveys to his or her bank (e.g. cheques).

Similarly, the government does not need a warrant to use "pen registers" and "trap and trace" devices, to record out-going and in-coming call information, because information about the number dialled and the time and duration of the call is accessible to third parties, mainly the telecommunications company (Cate 2007).

In the context of electronically stored data, the US government has routinely relied on this Third Party Exception to dispense with the warrant requirement. Federal courts take the view that a person does not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the subscriber information that he or she provides to an Internet service provider[27] . Therefore, the government was able to obtain the following personal information without a warrant:

- the name, address, e-mail address and media access control address from Comcast Cable Communications of a person who used Comcast's Internet services in the course of sharing movie files online[28];

- the information on an individual's computer that was accessible by a peer-to-peer file sharing program[29] ;

- the chat account information from Yahoo! of a person who used Yahoo's Internet services to access chat boards[30] ;

- the log-in information, including the date, time and IP address of each log-in, from Microsoft of a person who used Microsoft's MSN/Hotmail program[31]; and

- the contents of an iTunes files library shared over an unsecured wireless network[32].

At least one court took a different approach and held that whether a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy in subscriber information provided to an ISP depends in part on the ISP's terms of service[33].

Australian comparison

The Australian Constitution does not have any provision comparable to the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution which would put limits on Parliament's ability to pass search and seizure laws.

Generally, Australian search and seizure laws can be enforced subject only to the process and limitations, typically about procedure and justification or lack thereof, expressed in the relevant legislation itself ? legislation which can be amended, such as during the recent 'war on terror' when certain longstanding common law protections were diluted to some extent. (Roach 2010)

The Telecommunications Act 1997 for instance, discussed below, mentions but does not mandate warrants for s313(3) law enforcement help; reports suggest substantial collection of communications traffic data without warrants, including under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 (Cth). (Nicholls & Rowland 2007; Dobbie 2013)[34]."Doing your best" for 313(1) crime prevention purposes does not mention warrants; its proper ambit is unclear, and seems unlikely to be tested.

The Privacy Act 1988 may offer some procedural protections, although exceptions permit certain uses and disclosures for law enforcement and related purposes[35].These bypass questions of 'reasonable expectation of privacy' with simple statutory exceptions, and the Privacy Commissioner's policy Guidelines to their use. (OAIC 2014) A recent statement from the Privacy Commissioner in response to questions raised by reports of NSA programs in the US indicates a wide interpretation of the effect of obligations under domestic or foreign law enforcement laws in limiting protections under the Privacy Act; in the absence of determinations, this is also unlikely to be tested.

USA PATRIOT Act of 2001

Following the terrorist acts of September 11 2001, the Bush administration enacted the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 to expand government powers to obtain data for investigations related to international terrorism and other foreign intelligence matters.

Essentially, this Act had the effect of lowering previous thresholds for the activation of these powers in existing pieces of legislation by amending (a) the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978[36], and (b) other legislation governing National Security Letters. These controversial powers are discussed below.

Privacy and library groups also oppose the "library records request" provision of the Patriot Act on the grounds that it "leaves open the door for governmental misuse to broadly investigate library and bookstore patron reading habits"[37].

A reality check asking "who cares?" may however be appropriate at this point.

Many business operations think it irrelevant if a government wants to check their data in order to fight terrorism, provided the data is not damaged, lost, misused, or disclosed to competitors. So who would care?

- Governments typically do not want some of their information, of many types, to be accessible by other governments as a matter of principle, national security or sovereignty.

- Some businesses (say, a major miner) do not what their information to be accessible to the sovereign wealth funds (for example) of foreign powers.

- Other businesses may have specific reasons to be cautious about exposure to access, particularly if there is any suggestion of improper or overbroad access to or use of data beyond the purposes for these laws were put in place.

- Some entities may be willing to accept the initial access but remain concerned about further provision of data to other countries once it has been accessed under this method, due to the operation of other international instruments and agreements.

In any case, it may be harder for, say the US government to find information about an Australian entity hosted in a US data centre than it is to access or discover this information via a request from the US to Australia under various cooperation arrangements (below), and the operation of Australian law in response. Such options would limit the practical need to resort to this method.

Australian comparison

Following the Bali Bombings in 2002, Australia adopted a National Counter-Terrorist Plan (2003) and made extensive amendments to surveillance and access powers available to Government authorities[38].

These have somewhat less impact than the USA Patriot Act for our purposes, as they don't introduce administrative subpoenas per se, although there were considerable dilutions of existing protections, some comparable with US changes, and investigators gained extended powers and more streamlined procedures (Lynch & Williams 2006).

In subsequent years further legislative changes have somewhat further reduced the difference between thresholds in the US and Australia (Michaelsen 2010), and Australia's accession to the CoE Cybercrime Convention in 2012 requires enhanced cooperation with signatories, including the US, although this may make little practical difference ? see below.

Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA)

The US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act sets out a specific legal framework for surveillance operations conducted as part of investigations related to international terrorism and other foreign intelligence matters. With the introduction of the Patriot Act, the FISA was amended so that it now applies where a "significant" purpose of a surveillance operation is to obtain intelligence for the purposes of such investigations, rather than the "sole" or "primary" purpose, as it originally stipulated. More recent amendments have also broadened its use.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act framework will be activated where there is probable cause that the target of surveillance operations is, or is an agent of, a foreign power. Due to the Patriot Act amendments, terrorism is now included within the definition of "foreign power", and there is no requirement that targets of surveillance be engaged in any kind of criminal conduct. In addition, warrants for surveillance operations are issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), a closed forum separate from the standard federal court system.

Specific powers of law enforcement agencies under the FISA (as amended by the Patriot Act, Protect America Act of 2007, FISA Amendment Act of 2008, and reconfirmed in late 2012) that may constitute potential risks for those hosting data in the US include:

- The power of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to compel the production of any "tangible thing" for the purposes of an investigation to either obtain foreign intelligence or protect against terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities[39]. The FBI may do so by certifying to an FISC judge that the investigation falls within the bounds of the FISA and the judge does not have any discretion to refuse the order if certain procedural requirements are met[40]. Persons against whom such an order is made and/or sought are forbidden from disclosing these facts to any other person except for the purposes of complying with an order and/or seeking legal advice.

- The power to conduct secret physical searches of personal property for investigations in which foreign intelligence gathering is a significant purpose. The person whose property is searched need not be directly involved and the search may be conducted without a warrant, provided that the Attorney General certifies that there is no substantial likelihood the search will involve the premises, information, material, or property of a US person[41]. Subjects of a special search must not be informed of the fact that it has been or will be conducted, and third parties directed to assist must protect its secrecy.

- The power to obtain a search warrant in all criminal investigations without providing notice to the subject of the search for up to 30 days, or longer upon application to the Court if the facts justify further delay[42].

- The power to conduct roving wiretaps on communications lines, which allows for monitoring of several different communications lines across the US[43]. To engage in wiretapping, the government must obtain a warrant from the FISC based upon probable cause that the target is, or is an agent of, a foreign power[44]. Third party communications carriers, landlords and other specified persons must provide access and assistance necessary to carry out the warrant[45]. They must not reveal the fact of the warrant, and must minimize associated disruption to any services they provide to the subject. In the case of third party communications carriers, if a law enforcement authority suspects that the subject of a roving wiretap warrant might use a particular carrier's services, the authority is entitled to monitor all communications transmitted by that carrier. Accordingly, there is a risk that information concerning other clients of the carrier might incidentally be captured.

- The power of the Department of Justice (DOJ) to grant approval for law enforcement agencies to engage in electronic surveillance without a court order for up to one year for the purposes of obtaining foreign intelligence[46]. There must be no substantial likelihood that a US person is a party to the surveilled communications. Any third party carrier involved in transmitting the communications must assist the surveillance if requested, including by maintaining its secrecy[47].

- The power of the federal government to use "pen registers" and "trap and trace" devices to monitor outgoing and incoming phone calls for the purposes of an investigation to gather foreign intelligence information[48]. In some circumstances, relevant communications carriers may be obliged to assist authorities in installing and monitoring such devices, protecting the secrecy of the investigation and minimizing interruption to any services provided to the subject[49].

In June 2013 the Washington Post and Guardian published reports of 'data mining' targeting communications of non-US users for national security purposes, with only infrequent high level authorisations, based on broad interpretations of 2008 amendments to FISA. (Gellman & Poitris 2013) It was initially unclear the extent to which such programs, and the many others which followed, would affect business-oriented cloud data services. Several major consumer-oriented SaaS providers were reported to have agreed to participate, which could affect 'BYOD' devices, 'ad-hoc' clouds and cloud-enabled PCs, (Greenwald & MacAskill 2013) although details of the program and its implications remain in dispute at the time of writing, and some of the allegations have been denied.

'Administrative subpoenas' such as National Security Letters (NSLs)

National Security Letters are a type of federal administrative subpoena by which the FBI may, without court approval, compel individuals and businesses to provide a variety of records, including customer information from telephone and Internet service providers, financial institutions and consumer credit companies[50]. An NSL may be issued to any person (even if they are not suspected of engaging in espionage or criminal activity) so long as the issuer believes that they may hold information relevant to a clandestine terrorism or other intelligence investigation. The FBI does not need to specify an individual or group of individuals and each request may seek records concerning many people (Cate 2007). For example, nine NSLs in one investigation sought data on 11,100 separate telephone numbers (Cate 2007). Moreover, a recipient of an NSL may not reveal its contents or even its existence[51].

A communications carrier subject to a National Security Letter may be obliged to hand over information about a particular customer, their toll billing records and/or their electronic communications transaction records to the FBI[52]. However, there is no provision requiring a carrier to give the FBI access to the actual content of a client's communications.

National Security Letters have been the subject of considerable legal and political controversy. For example, a number of mandatory non-disclosure clauses have been ruled[53] unconstitutional (and subsequently re-enacted in a different form), and several reports by the US Inspector General have revealed widespread inappropriate use and underreporting by the FBI (Office of the Inspector General 2007).

(In March 2013, Judge Susan Illston of the Northern District of California declared, in a case involving the EFF, that 18 U.S.C. ? 2709 and parts of 18 U.S.C. ? 3511 were unconstitutional. She held that the statute's gag provision failed to incorporate necessary First Amendment procedural requirements designed to prevent the imposition of illegal prior restraints, and that the statute was unseverable and that the entire statute, also including the underlying power to obtain customer records, was unenforceable. The order was stayed subject to appeal[54]. While it could rein in the NSL model of access to network and cloud data to some extent, it remains to be seen whether this ruling survives appeal; or if it does, whether similar replacement provisions will be immediately re-enacted, resulting in minimal effective change.)

Australian comparison

There is no known direct equivalent of FISA and the very broad NSL administrative subpoena in Australia.

Certain provisions of recent anti-terrorism laws do restrict the capacity of those investigated to communicate this fact to their associates, but in relation to a limited range of specific offences. Certain provisions of the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth) and Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979, above, refer to national security purposes.

It is unclear what the impact of proposals for increased 'Data Retention' of telecommunications metadata would have if implemented, as no draft legislation was provided in by late 2013, and the Joint committee report declined to recommend it proceed. (JPCIS 2013) It is expected they would oblige increased retention so formal court orders could later be made for access to message contents, without necessarily diluting whatever existing requirements for such orders may be in place. There are however large numbers of warrantless metadata authorisations, over 300,000 in 2012-13, mostly by state police forces. (Attorney-General's Department 2012-13)

Reports in March 2014 suggest retention proponents remain enthusiastic. A Senate inquiry into the operation of the TIA Act, including this issue, is due to report in mid-2014, although with an unreceptive House of Representatives it appears unlikely its recommendations would be enthusiastically adopted.

The SWIFT case

A prominent example of the US government's use of an administrative subpoena is the SWIFT case. The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication is a Belgian-based co-operative active in the processing of financial messages, with about 8,000 banks as members. On average, it processed 12 million messages a day in 2005. SWIFT operated two primary data centres, an EU site reportedly in Belgium and a mirror site in the US. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the United States Department of Treasury (UST) addressed multiple administrative subpoenas to the SWIFT operations centre in the US under the "Terrorist Finance Tracking Program", requesting a copy of all the transactions in SWIFT's database, rather than just the records of individuals who were the specific targets of the government's investigation. (McNicholas 2009) SWIFT complied with the procedures by negotiating an arrangement whereby it transferred data from the mirrored SWIFT database to a "black box" owned by the US enabling the UST to perform focused searches over an extended period of time.

In late November 2006 the EU Article 29 Working Party[55] (the independent advisory body to the European Commission on data protection and privacy) issued an opinion on the processing of personal data by SWIFT concluding that SWIFT and the financial institutions which use SWIFT's services had breached Community data protection law as set out in Directive 95/46/EC, including the transfer of personal data to the United States without ensuring adequate protection and failure to inform data subjects about the way in which their personal data were being processed.

When this controversy developed in Europe, Australia and elsewhere in 2006 after the extent of UST searches over the transactions of European and other citizens became known, European data protection commissioners were ultimately unable to effectively intervene.

Although SWIFT itself is believed to have privately negotiated some constraints on the scope of searches over EU citizen transactions by US agents[56], SWIFT later formalised ostensible compliance with EU law by joining the US 'Safe Harbor' scheme. (The 'Safe Harbor' is a specific type of 'Adequacy Decision' adopted by decision of 26 July 2000 by the EC to allow the free flow of personal data between the EU and the US, in accordance with the EU Directive 95/46/EC[57]). This allows limitations on its data protection principles for important public purposes "to the extent necessary to meet national security, public interest or law enforcement requirements"[58]. The episode confirmed the limited options available to foreign data owners in the event of use of such administrative subpoenas.

Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA)

The ECPA is one of the primary federal statutes protecting the privacy of electronic communications in the US. (McNicholas 2009) Within the ECPA are the Wiretap Act, which prohibits the interception, use or disclosure of wire and electronic communications, and the Stored Communications Act (SCA), which regulates access to stored electronic communications. Consumer groups, privacy advocates and companies, including Microsoft Corporation, Google Inc. and E-Bay (the Digital Due Process Coalition) have criticized the ECPA as ineffective in protecting privacy in light of technological changes and are calling for the reform of the SCA.

The Stored Communications Act provisions at issue provide that the government needs to obtain a search warrant to gain access to the contents of an email that is 180 days old or less but can compel a service provider to disclose the contents of an email that is older than 180 days with only a subpoena (Salgado 2010).

Critics contend that the widespread use of email and other documents stored in the cloud are increasingly replacing the traditional ways of storing documents in paper form, on a hard drive or on a CD. They point out that information stored in traditional formats would be fully protected by the Fourth Amendment's warrant requirement, yet under the ECPA, "an email or electronic document could be subject to multiple legal standards in its lifecycle, from the moment it is being typed to the moment it is opened by the recipient or uploaded into a user's "vault" in the cloud, where it might be subject to an entirely different standard." (Beckwith Burr2010) Applying consistent standards is further complicated with regard to "Friend Requests, Status Updates and other forms of communication that are neither one-to-one communications, like email, nor public forum posts"[59].

Consequently, "courts have not been consistent in applying the Fourth Amendment's warrant requirement and the SCA's 180-day protection for communications in electronic storage to e-mail messages stored remotely on service providers' networks", which creates uncertainty for ISP's and other companies who host content with regard to how the ECPA applies to material on their systems[60].

For example, the Eleventh Circuit held that individuals do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in read e-mail messages stored with an ISP because they "shared" them with the service provider"[61]. In contrast, the Ninth Circuit held that an electronic communication service provider who turns over opened and stored text messages without a warrant or a viable exception is liable under the SCA for making an access that was not permitted "as a matter of law"[62]. To confuse matters more, a panel of the Sixth Circuit held that users have a reasonable expectation of privacy in e-mails, only to have its decision reversed by the Sixth Circuit sitting en banc on grounds that the plaintiffs did not have standing to sue, but without addressing the constitutionality of the SCA provisions[63].

As a result of the ambiguity in the law, the Digital Due Process Coalition has proposed the following changes to the ECPA:

- Treat private communications and documents stored online the same as if they were stored at home, and require the government to get a search warrant before compelling a service provider to access and disclose the information.

- Require the government to get a search warrant before it can track movements through the location of a cell phone or other mobile communications device.

- To require a service provider to disclose information about communications as they are happening (such as who is calling whom, "to" and "from" information associated with an email that has just been sent or received), the government would first need to demonstrate to a court that the data it seeks is relevant and material to a criminal investigation.

- A government entity investigating criminal conduct could compel a service provider to disclose identifying information about an entire class of users (such as the identity of all people who accessed a particular web page) only after demonstrating to a court that the information is needed for the investigation (Salgado2010).

Australian comparison

There is no broad Australian equivalent of the 'order to disclose' that is available to US federal government agencies.

However, some Australian government agencies possess similar powers under various legislative schemes. For example, the New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption may obtain certain information under State surveillance legislation, and CrimTrac[64] is listed as an 'enforcement agency' under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act.

Also note the proposals for 'Data Retention', mentioned above, introduced publicly in 2012. If implemented, these could require retention of communications metadata for periods of two years or more, which would facilitate local access under a subsequent court order.