Abstract

While most critiques of the Coalition Government?s National Broadband Network (NBN) policy have focussed on the wisdom of its Fibre to the Node technology choice, a more fundamental weakness in its NBN election policy promises to make it a financial debacle if not corrected. This paper spells out the many negative consequences of the Government's policy to remove the NBN Co's current monopoly in providing fixed broadband access infrastructure: to the federal budget, to the competition framework in telecommunications, to a forced premature sale of NBN Co, and to the affordable rollout of high-speed broadband access across the nation. The Minister of Communications is urged to correct this policy element rapidly, in the national interest.

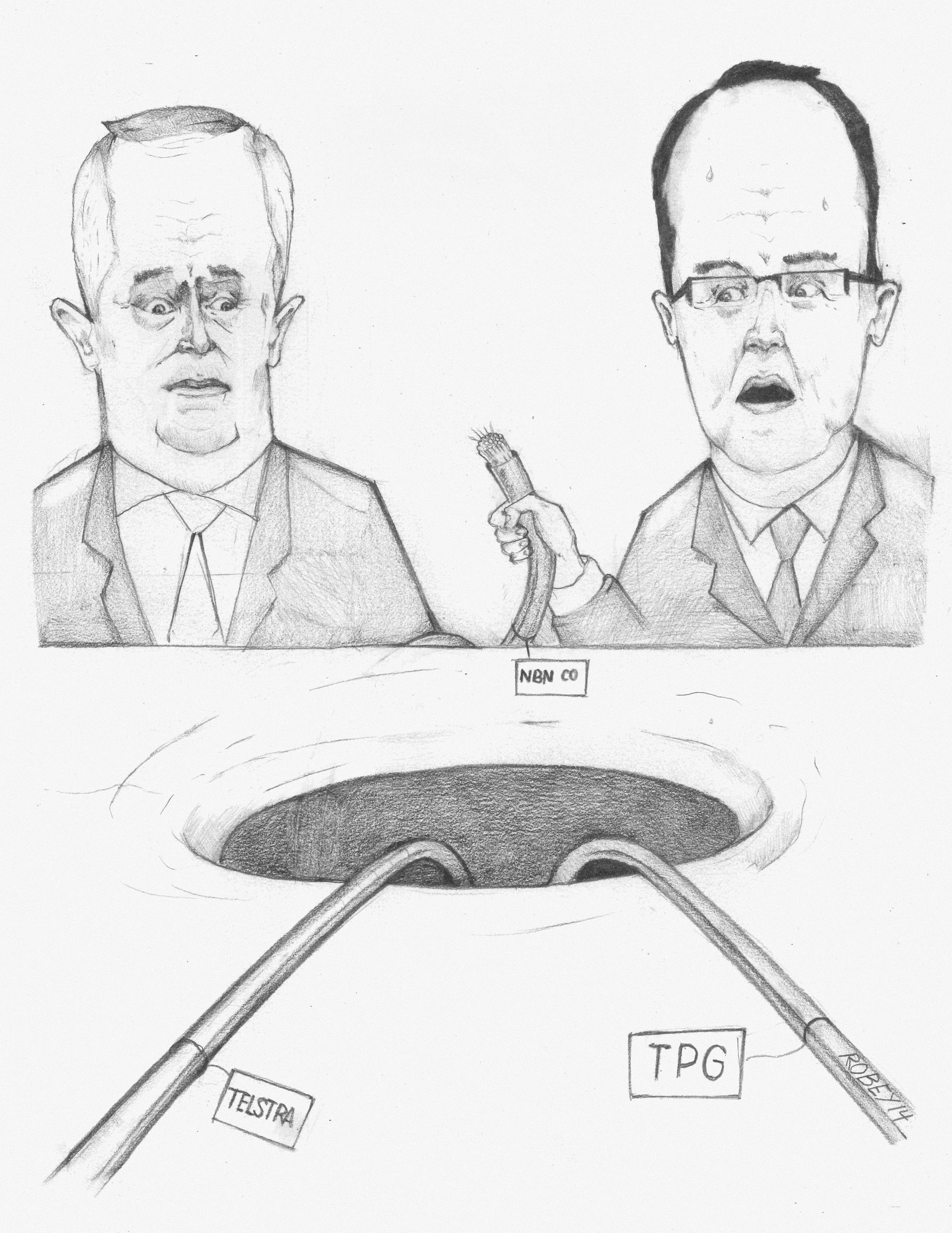

'Uh oh ' spoiler alert!' William Robey '2014

Introduction

The NBN is currently in the doldrums. Senior staff at NBN Co continue to leave the company, and Communications Minister Malcolm Turnbull has launched yet another audit review into the actions of the previous government (Stock and Land, 7 March 2013). While the rollout of the terrestrial and satellite-based radio implementations of the NBN continue as previously planned, the Minister has apparently departed from an election pledge (The Examiner, 17 August 2013) to honour all existing contracts to roll out fibre to the premises (the FTTP solution). Hence the recent demonstration by 30 contractors in Tasmania, who had invested in expensive new machinery to lay fibre, and now find their contracts to be worthless (ABC News, 27 Feb 2014).

Understandably the debate over the Abbott Government's new NBN policy (especially in this Journal) has tended to concentrate upon the costs and benefits of its fibre to the node (FTTN) policy in contrast to the previous FTTP policy or other technical solutions, e.g. (Eckermann 2013), (Gregory 2013), (Watkins & Lillingstone-Hall 2014) . After all, the future international competitiveness of Australia is allegedly at stake. But the Achilles heel of the Liberals' election promise on the NBN lies not with the short-termism of their technology choices. It lies in their policy decision to remove NBN Co's monopoly over the supply of fixed broadband infrastructure in the access network. The implication of this policy to undermine NBN Co's financial performance was first pointed out by the author on 10 April 2013 (Gerrand 2013) as part of a general critique of the then Opposition's NBN policy, launched on the previous day (Liberal Party 2013). This point has subsequently been argued more vigorously and, dare I say, more eloquently by industry commentators Paul Budde (2014) and Alan Kohler (2013, 2014).

I will now argue that the removal of the NBN Co's wholesale monopoly will not only push NBN Co's business case permanently into the red, it would also have several other significant negative consequences for the federal government. Or, to avoid that contingency, it would cause the Government to back off completely from its commitment to a ubiquitous high-speed NBN, and tempt it to an early sale of NBN Co to the private sector, if necessary at a fire-sale price, to move its liabilities off the federal budget. The more sensible approach will be for the Government to leave NBN's current wholesale monopoly intact.

The Coalition's NBN election policy

At the launch of the Liberals' NBN policy on 9 April 2013 (Liberal Party 2013), the then Opposition Leader Tony Abbott commended Mr Turnbull's policy as being 'very high quality work' and that it 'will provide a real commercial return' (Delimiter, 9 April 2013). It was indeed a commendably comprehensive election policy even if Mr Turnbull's paid consultants had done what consultants are always good at: inputting into their modelling the best case conditions (of costs, revenue and service performance) for their client's preferred solution and the worst case conditions for the alternative policy ' in this case, that of the then Government's. But by ignoring the effect of cherry-picking by NBN Co's competitors, the consultants failed to predict that, under this new policy, NBN Co will be doomed to run at a loss.

For some reason, perhaps driven by ideological preference rather than prudent economics, the Liberal's NBN election policy threw out the most essential economic underpinning element in the existing NBN's policy ' that of giving NBN Co a wholesale monopoly in the provision of fixed high-speed broadband access infrastructure. Thanks to that essential monopoly condition, the NBN can cross-subsidise broadband rollout in the poorest and the least densely populated areas of Australia.

And thanks to that essential monopoly, NBN Co can weather the storms of aggressive price control by the regulator (the ACCC), or disappointments in forecast revenue, or blow-outs in forecast costs. Because everywhere that the monopoly NBN infrastructure is in place, revenues will flow into the far foreseeable future from its Retail Service Providers; and by having access to sufficient profitable locations, NBN Co's business will eventually break even ' assuming that its wholesale pricing is regulated accordingly. At that point, with most of its network costs sunk, it will start generating an increasing annual profit for its long-term investor, the government. The penetration of broadband services across the community will rise, either slowly or rapidly, to eventually near-saturation levels, as occurred for the former standard telephony service in the 1990s and is now occurring in the mobiles market. The NBN pay-back period for the government may exceed early forecasts ' say 12 years or even 15 years, instead of ten ' but eventually, provided the wholesale pricing is well regulated, the project will produce a net positive return on investment.

But, some may ask, why must removal of the NBN's monopoly invariably cause it to run permanently at a loss'

The effect of cherry picking in the broadband infrastructure market

Once the NBN access infrastructure monopoly is broken, many entrepreneurial carriers will see the opportunities to cherry-pick the most profitable locations, such as for new apartment buildings or office blocks. In fact, TPG notably jumped the gun shortly after the September 2013 federal election by announcing its plan to build its own wholesale broadband network in built-up city areas, thereby relying on the Coalition Government's new policy before it had been tested in parliament, let alone legislated (Australian Financial Review, 18 September 2013). TPG's subsequent acquisition of AAPT in December 2013 for $419M was seen as further positioning itself to take advantage of the new government's NBN policy, while in the meanwhile claiming to have found a legal way around the current anti-cherry picking provisions.

The Minister's eventual public response to the TPG announcement (Australian Financial Review, 4 February 2014) suggests that he is well aware of what is at stake, and is waiting for the six month review of the cost and benefits of his NBN policy by a further panel of experts to decide which way to jump (Turnbull 2013). In the meantime NBN Co Chairman, Ziggy Switkowski has shown himself well aware of the potential revenue loss to his company (CommsWire, 13 March 2014).

Of course, if TPG is allowed to break the monopoly, the larger broadband infrastructure providers such as Telstra, Optus, NextGen and iiNet will feel entitled to follow. This will mean that NBN Co will be left with the least profitable segments of the metropolitan markets to serve, while being encumbered with serving highly unprofitable segments of the rural and regional market. Its annual losses could reach or exceed $2 billion per year, based upon worst-case revenue for the Coalition's current NBN business case (Liberal Party 2013), year on year until roll-out of the Government's proposed Fibre to the Node network is complete.

The implications of negative RoI for the government

If NBN Co under the anti-monopoly policy becomes as much a lemon as Aussat was in the 1980s under its no-compete-with-Telecom policy, its losses will mount up as a significant expense item in the government's annual Budget Operating Statement. But, because of the accounting convention whereby this item is treated as a 'below the line item' in the Operating Statement (Dalzell 2012), it will not embarrass the government politically by pushing the Budget Deficit ' that headline figure ' further into the red. On the other hand, the NBN's net losses will directly affect the government's overall fiscal balance ' as you would expect.

Parliamentary Library researcher Brian Dalzell (2012) points out that: 'A (fiscal) deficit indicates that the government is drawing on resources from other sectors in the economy'. In other words, the longer that NBN Co remains loss-making, the longer the NBN itself needs to be cross-subsidised ' ultimately by the rest of the economy. Gone are the days of the expected 7% long-term Return on Investment (RoI) from a self-funding national infrastructure project.

Just how long Federal Treasurers and Federal Ministers of Finance from either side of the political divide would be prepared to tolerate such a financial albatross is easy to guess.

The impact of the broken monopoly on regulatory policy

Beyond the ongoing financial damage which the Coalition's current NBN policy will do to the Government's budget lies the collateral damage of regulatory confusion. Once Telstra feels obliged ' in the interests of its shareholders ' to follow TPG in leveraging its great assets in network deployment to offer fixed broadband access infrastructure in competition with NBN Co, the whole issue of unfair advantage of the dominant retail provider being also a dominant provider of wholesale broadband access will emerge again. This was the issue which bedevilled the industry for the duration of the Howard government, stifling competitive broadband infrastructure investment, and which most of the industry believed was neatly solved by Labor's 2009 NBN policy: Telstra was effectively paid out $11 billion for vacating the copper access network, with a no-compete clause on most wholesale broadband fixed infrastructure access via other technologies.

How to heal the Achilles' heel'

The Abbott Government has several options:

The most obvious choice is to revise its policy, in order to maintain the NBN monopoly on fixed access infrastructure ' which requires no legislative change. The advantages are manifold: a reduction in the NBN's losses that would otherwise keep dragging down the federal budget; a long-term positive return on investment that will provide ever increasing federal revenue once the break-even year is reached; the opportunity to use NBN Co for cross-subsidisation of wholesale prices, thus keeping voters in the regions ' and in the outer suburbs of our large cities ' onside.

Furthermore, it will maximise the value of NBN Co when the Government moves to sell it off to the private sector (a policy which I would argue is not in the national interest, but it is one which suits the current major parties' neo-liberal philosophies).

An alternative choice for the Government is to stick to its anti-monopoly policy, driven by the desire to keep faith with its supporters as well as those corporations, such as TPG, which have already made investment decisions based on the assumption that the election policy will indeed be implemented.

In that case the Government will need to deal with the downsides detailed above.

To avoid the resultant drag on the federal budget of the order of $2 billion p.a. for several years, the government will be motivated to sell off NBN Co as soon as possible.

However, NBN Co will be unsellable while it maintains the liabilities inherent in the Abbott Government's current NBN policy ' i.e. in providing a truly national rollout of high-speed fixed broadband infrastructure while running at a loss. To make NBN Co saleable, the Government would be forced to significantly dilute its obligations to provide a universal high-speed broadband service ' most likely by heavily increasing the user-pays component.

Conclusion ' the need to correct that policy blunder

This article has described in some detail why the intention to break NBN Co's current wholesale monopoly is the Achilles heel in the Turnbull-Abbott election policy ' and needs urgent revision.

This is not a lone voice. While the author drew attention to this weakness in the policy first on 10 April 2013 (Gerrand 2013), other industry analysts have agreed (e.g. Budde 2014). Allan Kohler has argued eloquently for the abandonment of this policy in two columns (2013, 2014). In fact Kohler has memorably described the Turnbull NBN policy in these terms:

'It will, in short, be a donkey, a money sinkhole, a political noose, and an end-of-career nightmare for a mild-mannered nuclear physicist who might end up wishing he'd stayed at the opera.' (Kohler 2013)

The current article goes further in drawing attention to the additional implications if this policy is not corrected ' especially the implications for Australia if, as a consequence, NBN Co is sold off prematurely, freed of its current obligations to provide broadband access infrastructure across the country, in order to make the company saleable.

Such a sell-off would simply create another Qantas ' a privatised entity legally obliged to give first priority to serving its institutional shareholders, while being hobbled by a caveat on foreign ownership to placate an increasingly disgruntled electorate. And just as the Qantas Board has been forced since its privatisation to abandon unprofitable rural and international services, a privatised NBN Co, having to compete with carriers with much deeper pockets, will inevitably be forced to ditch any further attempts at cross-subsidies to provide equity in access to outer suburbs and regional population centres.

In short, unless the Minister for Communications acts to correct this fundamental error in his NBN policy, we will live to see another great Australian policy disaster. The most important objective of the NBN, the only one that justifies government investment of the order of $30 billion or more, will be abandoned: that is, to make Australia internationally competitive ' across the nation, not just in central business districts and technology parks ' in its ability to succeed in the new digital economy.

References

ABC News, 'Tasmanian NBN contractors seek compo over fibre optic rollout changes', ABC News online, 27 February 2014, at http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-02-26/tasmanian-nbn-contractors-seek-compo-over-fibre-optic-rollout-c/5285112

Australian Financial Review [David Ramli and James Hutchinson]. 2013. 'TPG fibre plan challenges NBN', 18 September 2013, at http://www.afr.com/p/australia2-0/tpg_fibre_plan_challenges_nbn_v10TzlbnSJEHWqPQ70CZ3K

Australian Financial Review [David Ramli]. 2014. 'Turnbull queries TPG bid to skirt NBN', 4 February 2014, at http://www.afr.com/p/business/companies/turnbull_queries_tpg_bid_to_skirt_FRzXpQsdo1IkyjjqSRV5EI

Budde, Paul. 2014. 'No NBN cherry picking ' another step in the right direction', BuddeBlog 10 February 2014, at http://www.buddeblog.com.au/frompaulsdesk/no-nbn-cherry-picking-another-step-in-the-right-direction/

CommsWire [David Swan and Graeme Phillipson]. 2014. 'Ziggy fires TPG warning shot' ' CommsWire, No. 1295, 13 March 2014, at www.commswire.itwire.com

Dalzell, Brian. 2012. 'The national broadband network and the federal government budget statements', Australian Parliamentary Library Background Notes, 13 January 2102, at http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BN/2011-2012/NBNBudgetStatements

Delimiter. 2013. 'Coalition NBN policy launch: Full video', 9 April 2013, at http://delimiter.com.au/2013/04/09/coalition-nbn-policy-launch-full-video/

Eckermann, Robin, 2013. 'Getting some reality into debates about NBN FTTP'. Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, Vol 1, No 1, Article 13. http://doi.org/10.7790/ajtde.v1n1.13

Gerrand, Peter. 2013. 'The Coalition's NBN policy is a triumph of short-termism over long-term vision', The Conversation, 10 April 2013, at http://theconversation.com/the-coalitions-nbn-policy-is-a-triumph-of-short-termism-over-long-term-vision-13333

Gregory, Mark. 2013. 'A flexible upgrade path for the Australian National Broadband Network', The Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, Vol.1 No.1, Article 17, November 2013, at http://doi.org/10.7790/ajtde.v1n1.17

Kohler, Alan. 2013. 'The NBN Board has run away. Why'', Business Spectator, 23 September 2013, at http://www.businessspectator.com.au/article/2013/9/23/information-technology/nbn-board-has-run-away-why

Kohler, Alan, 2014. 'Sorry Malcolm, the NBN must be a monopoly', Technology Spectator, 3 March 2014, at http://www.businessspectator.com.au/article/2014/3/3/technology/sorry-ma...

Liberal Party. 2013. 'Fast, affordable, sooner. The Coalition's plan for a better NBN', 9 April 2013, at https://www.liberal.org.au/fast-affordable-sooner-coalitions-plan-better-nbn

Stock and Land [Lia Timson], 2014. 'Malcolm Turnbull starts fifth NBN audit', Stock and Land, 7 March 2014, at http://www.stockandland.com.au/news/metro/national/general/malcolm-turnbull-starts-fifth-nbn-audit/2690792.aspx

Turnbull [The Hon. Malcolm Turnbull MP, Minister for Communications]. 2013. 'Panel of Experts to conduct cost-benefit analysis of broadband & review NBN regulation', 12 December 2013, at http://www.minister.communications.gov.au/malcolm_turnbull/news/panel_of_experts_to_conduct_cost-benefit_analysis_of_broadband_and_review_nbn_regulation#.UyVAI9yyKMW

The Examiner [Ben McKay]. 2013. 'Turnbull confirms NBN will honour contracts', The Examiner, 17 August 2013, at http://www.examiner.com.au/story/1711548/turnbull-confirms-nbn-will-honour-contracts/

Watkins, Craig; Lillingstone-Hall, Kelvin. 2014. 'The FTTdp Technology Option for the Australian National Broadband Network', The Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, Vol.2 No.1, March 2014, at http://doi.org/10.7790/ajtde.v1n1.6