Abstract

The history of the landmark UDRP (Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy) decision in 2006 on <andalucia.com>, related as a memoir by the key protagonist who developed and operated the <andalucia.com> website, shines light on an important legal precedent for the acceptance of non-governmental use of significant geographical names in the Internet Domain Name System. The narrative is supplemented by an overview of the development of geographical names policy in the domain name system from its inception through the development of ICANN?s Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), and how Panelists applied it to geographical name disputes including references to the first and second WIPO reports.

Andalucia.com: the beginning

On 17 April 1996 I telephoned U-Net to place an order for web hosting space and to register the domain name <andalucia.com>. The following day the domain was live and I uploaded pages to a new website that I simply called ?Information about Andalucia?. Andalucia is the name of the large region of southern Spain, extending from the Portuguese border in the west to the province of Almer?a in the east, where I had resided since 1991. It became the second largest of Spain?s 17 Autonomous Regions in 1980, following the death of General Franco and the return to democracy with a constitutional monarchy in 1978. My interest was in documenting Andalucia in photographs, and providing information for tourists, since there was almost nothing available on the Internet at that time.

At this time the only generic top level domains (gTLDs) available for general registration were .com, .net and .org. The second level registration of a new domain name was achieved by emailing a template form to Internic. Payment was made several weeks later, on receipt by post of an invoice for US$100 covering two years? registration. There was no web registration nor any web ?whois? interfaces. Domain name allocation was on a first-come first-served basis. This was a simple IANA policy based on entitlement to register, created in an earlier era when there were no registration fees and a technical community who only registered what they needed, no more. At this time there was no mindset to register for resale and profit. There were only a handful of reserved names, a first group reserved for technical reasons and a second group which US authorities judged to be obscene[1] (Forrest 2013: chapter 3).

The project continued to grow. I worked on website design work for clients during the week, while at weekends I travelled extensively around Andalucia collecting information and taking photographs. In January 1997 a man called Lou Dinella, of Bravo Tours in New Jersey, contacted me to ask the price for linking from <andalucia.com> to his website. The concept of selling advertising on the <andalucia.com> website was created.

In early 1997 I visited the offices of the ?Instituto de Formento de Andalucia?, a part of the Department of Transport and Industry of the Junta de Andaluc?a (Regional Government). I formally applied for a grant to help build my tourist information website on the domain <andalucia.com>. I recall the gentleman showed very little interest in the project, saying it would never take off, and the grant was not approved.

The website became popular because we provided detailed, well-researched information written by professional magazine and guidebook journalists. We understood what tourists wanted to read. Numerous other websites began to link to <andalucia.com> for the useful information it provided. We took on our first employee, Mike Cartwright, in July 1998.

ICANN and WIPO

In June 1998 the US Government published its White Paper (NTIA 1998) which led to the creation of ICANN to manage the Internet?s naming and addressing. It included in section 8:

The Trademark Dilemma. When a trademark is used as a domain name without the trademark owner's consent, consumers may be misled about the source of the product or service offered on the Internet, and trademark owners may not be able to protect their rights without very expensive litigation.

Response: The U.S. Government will seek international support to call upon the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) to initiate a balanced and transparent process, which includes the participation of trademark holders and members of the Internet community who are not trademark holders, to (1) develop recommendations for a uniform approach to resolving trademark/domain name disputes involving cyberpiracy (as opposed to conflicts between trademark holders with legitimate competing rights).

The following year WIPO published its ?Final Report on the First WIPO Internet Domain Name Process? (WIPO 1999). Whilst it recognised the existence of the Domain Name Dispute Policy used by Network Solutions Inc. (NSI) (the sole registrar and registry of the .com, .net and .org gTLDs), this was overly mechanical and the immediate solution was to put a domain name on hold. A subsequent court order was required to make a transfer of ownership of the domain. WIPO recommended that ?ICANN should adopt a dispute-resolution policy under which a uniform administrative dispute-resolution procedure is made available for domain name disputes in all gTLDs.?

Geographical names were considered to be outside the scope of the report. ?Other issues remain outstanding and require further reflection and consultation. Amongst these other issues are: the problem of bad faith, abusive domain name registrations that violate intellectual property rights other than trademarks or service marks, for example, geographical indications and personality rights? (WIPO 1999)

The ICANN Board accepted the WIPO report and requested that their Names Council produce a policy to deal with the issue. In October 1999 the ICANN Board approved the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), still hailed as one of ICANN?s most successful policies (ICANN 1999). One month later WIPO was approved by ICANN as the first dispute provider and within days the first complaint, re <worldwrestlingfederation.com>[2], was received.

After five months WIPO had received about 550 complaints under the policy. Many included well known brands, such as <f1.com>, <easyjet.net>, <Telstra.org>, <banesto.net>, <dior.org>, <jpmorgan.org>, <tata.org>, <Microsoft.org>, <abta.net> and <niketown.com>. There were a few complaints that included a geographical element where the complainant held trademarks for products such as <timesofindia.com> and <raimat.com>[3] or real estate developments such as <ashburnvillage.com>[4]. There had been a handful of cases in French courts <santropez.com> and <laplagne.com> and German and Swiss courts respectively <Heidelberg.de>, <berner-oberland.ch> and <luzern.ch>, all resulting in transfer of ownership to the city authority or agency. There had been no complaints relating to geographical names brought under the UDRP thus far.

On June 28 2000, WIPO received a letter (Alston 2000) from the Government of Australia and 19 of WIPO?s other member governments, seeking to initiate a Second WIPO Process to address certain intellectual property issues including geographical indications, geographical terms and geographical indications of source (e.g. for the Champagne region).

Andalucia.com gains distinctiveness

In early 2000 a distinctive <andalucia.com> logo was designed by Joaquin Dominguez. The logo is reproduced here:

Figure 1. The logo for andalucia.com

By now the company had several employees, including a dedicated sales team, web designers and administration staff. In May 2000 we reached 20,000 unique visitors a week, reading 100,000 pages a week. This was the highest for any website about Spain.

Clearly our brand was gaining distinctiveness. We decided to register a trademark in Spain. On the 27 July 2000 we approached Ungria, the trademark agents in Madrid, about a Spanish trademark for the company.

On 1 August 2000 they gave us important advice that I still believe to be relevant today: ?Andalucia can never be monopolised by anybody as an exclusive title. Furthermore Spanish trade mark law actually expressly prohibits this? but ?as a graphic Andalucia with the .com and the three @ inside a circle forms a distinctive unit and can be registered?.

We instructed Ungria to proceed with registration. On 16 April 2001 came the news that our application had been ?suspended? because the Junta de Andalucia had objected on the grounds of similarity to the ?JUNTA DE ANDALUCIA? trade mark (1,124,069 & 2,105,103) and the ?A ANDALUCIA? trade mark (1,641,600). Ungria presented our case to the Spanish Trademark Agency OPEM but it was rejected. On 18 April 2001 Ungria wrote to us suggesting we appeal as a different examiner might take a more reasonable view. However we decided not to pursue the matter due to additional costs.

The barcelona.com case

<Barcelona.com>[5] was registered in February 1996 and on 26 May 2000 WIPO received a complaint under the UDRP: the first UDRP geographical name dispute. The Barcelona city council did not have a descriptive trademark for the term ?Barcelona? in Spain (Spanish trademark law[6] prohibited registration of marks consisting exclusively of ?geographical origin?) or elsewhere. However it did have various trademark registrations which included ?one main element, namely the expression ?BARCELONA"".

Under Section 4(a) of the UDRP, a domain name registration is abusive on proof of the following three elements:

(i) the Registrant?s domain name is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which the Complainant has rights;

(ii) the Registrant has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain name; and

(iii) the Registrant?s domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith.

The Panel found that the Complainant did have trademark rights under UDRP section 4(a)(i) on the basis that the ?distinctive character? of the Complainant?s mark was the name ?Barcelona?.

There was no website at the Barcelona.com address when the complaint was filed and the Panel did not accept the Respondent?s evidence of planned website business activity as a legitimate interest under UDRP section 4(a)(ii).

In the third test in 4(a)(iii), the Panel?s finding on bad faith usually follows the line of the first two and does not change the outcome itself. In this case the Panel concluded on a negative note, ?to put in doubt the existence of good faith at the time the Respondent obtained the registration of the domain name?.

All three elements being proved, the domain was transferred to the Complainant. (It was later returned through use of the different criteria of the United States Federal trade mark law, the Lanham Act,[7] which protected, the registrant, a USA company in the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals.[8])

The second UDRP case was <stmoritz.com>[9] where the city did have ?St. Moritz? as a registered trademark in 27 countries and the panel did ?find that the Domain Name is identical to the trademark "St. Moritz" of the Complainant giving rights under UDRP section 4(a)(i)?

In this case the website owner did not submit a response to WIPO. The Panel looked at the website on the domain and reported that ?Respondent provides informational services about the city of St. Moritz and about Switzerland." So they found it "does qualify as a bona fide activity" and that the ?Respondent may have legitimate rights? under UDRP section 4(a)(i)?

Of the third UDRP element the Panel found that ?the circumstances present do not indicate that the Respondent would have registered and is using the Domain Name in bad faith.?

Only the first of the three elements being proved, the Complaint was denied.

During the 15 months following publication of the <Barcelona.com> and <stmoritz.com> case decisions, governments or their agencies brought 28 geographical term WIPO UDRP cases[10]. This number tailed off over the subsequent four years (9, 7, 7 and 1 from 2002 to 2005) as clear patterns emerged.

In 2005 WIPO also published an overview which clarified the consensus view that "Some geographical terms however, can be protected under the UDRP, if the Complainant has shown that it has rights in the term and that the term is being used as a trademark. Normally this would require the registration of the geographical term as a trademark." and added "It is very difficult for the legal authority of a geographical area to show unregistered trademark rights in that geographical term on the basis of secondary meaning" (WIPO 2005).

In short, to be successful the Complainant needed an identical or very similar registered trademark, whereas the Respondent only needed a website with some information about the place.

The second WIPO report

Meanwhile the Second WIPO Internet Domain Name Process addressed the outstanding issues through a process of consultations and the result was a final report published on 3 September 2001. Section 6 covers the subject of geographical names; half of the section covers protection for geographical terms per se, as opposed to geographical indications in the source of goods and services.

The report acknowledged evidence of the misuse of geographical domain names, citing case examples where the website content ?bears no relationship with the geographical indication? and where the registration was ?with a view to preventing others from registering the same name?. This report observed, after less than two years of UDRP cases, that they ?do not necessarily stand for the proposition that the registration of a city name or the name of a region, as such, is to be deemed abusive? (WIPO 2001).

It presented an analysis of country names, and city names using a UNESCO World Heritage list, underlining two points that governments were fundamentally uncomfortable with:

- The overall majority of country names . . . have been registered by persons or entities that are residing or located in a country that is different from the country whose name is the subject of registration.

- In almost all cases . . . the registrant is a private person or entity. Only rarely is it a public body or an entity officially recognised by the government of the country whose name has been registered.

The WIPO second report highlighted that there were ?fundamental problems in endeavoring to apply the existing international legal framework to prevent the bad faith misuse of geographical indications in the Domain Name System (DNS)...? in respect of applicable law because of the different systems that are used, at the national level, to protect geographical indications.? It was suggested that ?These problems of applicable law could be avoided if a multilaterally agreed list of geographical indications were to be established.?

244. It is recommended that no modification be made to the UDRP, at this stage, to permit complaints to be made concerning the registration and use of domain names in violation of the prohibition against false indications of source or the rules relating to the protection of geographical indications.

As Governments did not support this recommendation, picking up on WIPO?s need for a new law to enable progress to be made, and the uncomfortable analysis that the Paris Convention[11] did not expressly prohibit country names as trademarks, the Member States subjected WIPO?s second report to WIPO?s Standing Committee on the Law of Trademarks, Industrial Designs and Geographical Indicators. Special sessions were held in December 2001 and May 2002 and its recommendations were transmitted by letter to ICANN (Gurry 2003):

Country Names It was recommended that this protection should be implemented through an amendment of the UDRP and should apply to all future registrations of domain names in the gTLDs.[12]

|

|

|

|

|

|

On 13 March 2006, ICANN informed governments that it had not been possible to achieve consensus among ICANN?s constituencies concerning the recommendations of the Second WIPO Internet Domain Name Process (ICANN 2006). The UDRP remained unmodified in its original and basic form ? as discussed in detail in (Forrest 2013: chapter 3).

The andalucia.com case

Meanwhile, back in Andalucia, completely unaware of what had been happening at WIPO and ICANN, I continued to build the andalucia.com website business, and in April 2006 we celebrated our 10th anniversary. By this time the website was receiving approximately 300,000 unique visitors a month viewing around 1.6 million pages. The company behind it had also grown to employ 12 full time and two part-time members of staff and was supported by five journalists. We had moved into new offices in Estepona in the province of M?laga.

Thus it was with great surprise that on the evening of Wednesday 14 June 2006 I received an email about a WIPO complaint, on behalf of the Tourist Board of the regional government, the Junta de Andalucia.

After some intensive study of the ICANN and WIPO websites, we started to compile a shortlist of possible lawyers to act on our behalf. We sent out emails on the following Sunday and were impressed to receive a few replies the same day. We set up a call with Matthew Harris of Norton Rose in London (now with Waterfront Solicitors) on the Monday and engaged him later that day. Matthew requested support from Spanish lawyers. Since it proved to be difficult to find an Intellectual Property lawyer in Andalucia willing to take on the case, I travelled to Madrid to meet and engage a leading firm who insisted that their name not be associated with the case.

Trademark Rights

The UDRP Panel reported that[13] the Complainant (Tourist Board of Andalucia) owned many registered trademarks which included the word ?Andaluc?a? as part of a number of words. The case focused on a trademark consisting of the stylised word ANDALUCIA below a badge-shaped logo comprising a stylised letter ?A? in white on a part blue, yellow and green background, registered on 10 June 1991 as follows.

Figure 2. The Andalucia trademark

The Complainant clearly had rights in the trademark as registered. But does such a ??word and design? registration give the Complainant rights over the geographical indication ANDALUCIA?

We, as the Respondent, argued[14] that the mark and the word were not identical; ?even if one discards the graphical elements of the mark, what is left is not the word "Andalucia" but the phrase "A Andalucia" which translates roughly in English as "To Andalucia". (Indeed, the intent of the trademark designer appears to be a moderately clever play upon the fact that the word for "to" in Spanish is also the first letter of the word "Andalucia".)

The Panel reviewed a number of cases that the Complainant referred to as supportive but found that none of these cases were determinative.

The Panel found that the Complainant did have trademark rights under UDRP section 4(a)(i) and explained the rationale.

?Although the Panel believes it is a close call, the Panel concludes that at least as to the A ANDALUCIA word and design mark, ANDALUCIA is the dominant feature in the mark. Therefore, the Panel finds that the domain name at issue is confusingly similar to a mark in which Complainant has rights.?

Legitimate interests

There had been a website about Andalucia on the domain for the entire time since it had been registered. In view of all previous case decisions I still wonder how the Complainant could possibly have made a valid case for lack of legitimate interests.

Here the Complainant focused on its trademark, again stating that we had no rights or legitimate interests because the ?Respondent knew or should have known of Complainant?s registered marks.?

The Respondent also highlighted its own trademark, but the fundamental right and legitimate interests were that it has expended resources over the years in the development of the informational website about Andalucia. Additionally the Complainant, knowing of Respondent?s website, failed to object for at least five years to Respondent?s use of the domain name.

Predictably the panel found legitimate interest under UDRP section 4(a)(ii).

?Respondent is using a geographical indication to describe his product/business or to profit from the geographical sense of the word without intending to take advantage of Complainant?s rights in that word, then the Respondent has a legitimate interest in respect of the domain name.?

Bad faith

The Complaint contended that the ?Respondent has registered and is using the domain name at issue in bad faith since it has no licence or other permission of the mark owner to use the mark in a domain name. ?

The Respondent contended that it ?did not register the domain name at issue in bad faith, since at the time it registered the domain name it did not know of Complainant?s mark? and it did not ?use the domain name in bad faith, since it had no idea that Complainant objected to its use of the domain name at issue until it received a copy of the complaint in this matter.?

The Complainant also made some startling claims for a Destination Marketing Organization (DMO) about the alleged concentration of information on the website about the upmarket resort town of Marbella whilst ?virtually ignoring all other provinces or regions of Andalucia and only mentioning for sales purposes some of the distinctive items of this internationally famous region such as olive oil and serrano ham, and basically treating the most symbolic aspects of Spanish culture such as flamenco and mozarabic art with little respect.? In the response we had a duty to prove these allegations to be false by detailing relevant website pages.

The Panel found that Complainant had failed to establish any of the bad faith circumstances that the domain name was registered or being used in bad faith.

Accordingly, the Panel found that the Complainant had failed to satisfy its burden of proof and the complaint was denied.

Reverse Domain Hijacking

The Respondent requested a finding of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking, alleging that the complaint in this matter was filed in bad faith. Despite the Respondent filing ten detailed points to support this claim the Panel did not find against the Complainant, nor give any detailed rationale to explain their decision.

Conclusion: the legacy

?Landmark decisions such as <newzealand.com> and <andalucia.com> set a precedent of recognising non-governmental interests in geographical names? use in the Domain Name System. Decisions such as <brisbane.com> and <rouen.net> and <rouen.com> have unequivocally elucidated that government use of a geographical name is not equivalent to trademark rights, the only form of right protected by DNS rights protection policy.? (Forrest 2014).

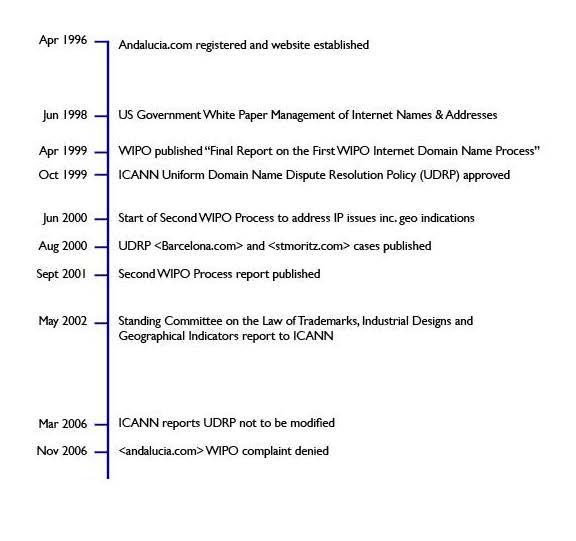

Andalucia.com was also an unusual case. It was about control of a domain name over a leading website that had built up substantial traffic and influence over ten years. The timeline for this case is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Timeline for the andalucia.com WIPO/UDRP case.

The UDRP panel comprised three panelists who were very experienced in the field, and whose landmark decision finally defined the UDRP landscape in respect to geographical names. In the eight years since there have only been three cases brought to WIPO.

At this time the applicable law has not been changed as requested by the second WIPO report, nor has the UDRP been revised. Governments still do not find this a very satisfactory situation and have channeled their concerns through ICANN?s Government Advisory Committee (GAC) (Forrest 2014).

Looking ahead: 900 gTLDs

Shortly after the <andalucia.com> case the new generic Top Level Domain (gTLD) program was given approved by ICANN board and in early 2014 the first of the 900 new open domains (for example: .guru, .bike .photography, .estate) are accepting general registrations at the second level. Will this lead to another wave of UDRP cases in geographical names?

On one hand the Governments? Destination Marketing Organisations (DMOs), who brought most of the past UDRP complaints, have had six years to ensure their trademarks are in place. On the other hand, the website owners have also had this time to understand the need to feature information about the destination on their domains. Happily, publishing this information is also perfectly in line with the mission of the DMOs.

The distinctive green <andalucia.com> brand website continues to grow at an ever increasing rate, and we remain guardians of a nine character string in the .com zone of the DNS of the Internet.

References

Alston, Senator Richard. 2000. Letter from Richard Alston, Minister for Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, Government of Australia to Dr Kamil Idris, Director General, World Intellectual Property Organization.

http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/processes/process2/rfc/letter2.html

Forrest, Heather. 2013. Protection of Geographic Names in International Law and Domain Name System Policy. Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands: Kluwer Law International.

Forrest, Heather. 2014.?Geographic Internet domains -- Issues in the developing DNS?. Australian Journal of Telecommunication and the Digital Economy, 2(1), March 2014.

Gurry, Francis. 2003. Letter from Francis Gurry, Assistant Director General, Legal Counsel, WIPO to Dr. Vinton G. Cerf, Chairman, ICANN (February 21, 2003). At http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/amc/en/docs/wipo.doc

ICANN. 1999. Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy. [Internet] As approved by ICANN on October 24, 1999. Accessed 7 February 2014. Available from http://www.icann.org/en/help/dndr/udrp/policy.

ICANN. 2006. Letter from Dr Paul Twomey, President and CEO, ICANN to Mohamed Sharil Tarmizi, Senior Advisor, Office of the Chair, Government Advisory Committee of ICANN, 13th March 2006. Available from http://www.icann.org/en/news/correspondence/twomey-to-tarmizi-13mar06-en.pd

NTIA 1998. Management of Internet Names and Addresses. National Telecommunications and Information Administration, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE. Available from: http://www.icann.org/en/about/agreements/white-paper

WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization). 1998. ?Interim Report of the WIPO Internet Domain Name Process, 'The Management of Internet Names and Addresses: Intellectual Property Issues?. [Internet]. Published 23 December 1998. Accessed 7 February 2014. Available from: http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/processes/process1/rfc/3/index.html

WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization). 1999 The Management of Internet Names and Addresses: Intellectual Property Issues. Final Report of the WIPO Internet Domain Name Process April 30, 1999. Available from: http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/amc/en/docs/report-final1.pdf

WIPO. 2001. Second WIPO Internet Domain Name Process: The Recognition of Rights and the use of Names in the Internet Domain Name System. WIPO September 3, 2001. Available at: http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/processes/process2/report/html/report.html

WIPO. 2005. Overview of WIPO Panel Views on Selected UDRP Questions, Original Edition (2005) Available from: http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/search/oldoverview/

Notes

[1] These were the thirteen words forbidden on US television.

[2] World Wrestling Federation Entertainment, Inc. v. Michael Bosman <worldwrestlingfederation.com> WIPO Case No. D1999-0001 (18-01-2000) http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/decisions/html/1999/d1999-0001.html

[3] Raimat, S.A. v. Antonio Casals <raimat.com> WIPO Case No. D2000-0143 (02-05-2000) http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/decisions/html/2000/d2000-0143.html

[4] Ashburn Village Development Corporation & Bondy Way Development Corporation v. Re/Max Premier WIPO Case No. D2000-0322 20-06-2000 http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/decisions/html/2000/d2000-0322.html

[5] Excelent?simo Ayuntamiento de Barcelona v. Barcelona.com Inc. WIPO Case No. D2000-0505 (Aug. 4, 2000), http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/decisions/html/2000/d2000-0505.html (last visited Jan. 10, 2014).

[6] Spanish Trademark Law of 1988, Art. 11(1)(c)

[7] Lanham Act ?? 32, 45, as amended, 15 U.S.C.A. ?? 1114, 1127.

[8] Barcelona.com, Inc. v Excelent?simo Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 330 F.3d 617 (4th Cir, 2003).

[9] Kur- und Verkehrsverein St. Moritz v. StMoritz.com WIPO Case No. D2000-00617 August 17, 2000 http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/decisions/html/2000/d2000-0617.html

[10] Index of WIPO UDRP Panel decisions? Category II.A.1.k.(ii) Geographical Terms http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/search/legalindex.jsp?id=11250.11280

[11] Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property. March 20, 1883 and revised and amended to September 28, 1979 http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/paris/trtdocs_wo020.html

[12] The decision on the protection of country names was supported by all Member States of WIPO, with the exception of Australia, Canada and the United States of America, which dissociated themselves from the decision. Japan also expressed certain reservations, which are recorded in the text of the decision

[13] Junta de Andalucia Consejer?a de Turismo, Comercio y Deporte, Turismo Andaluz, S.A. v. Andalucia.Com Limited, WIPO Case No. D2006-0749 (Oct. 13, 2006) http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/decisions/html/2006/d2006-0749.html

[14] Response in WIPO Case number D2006-0749. (Unpublished)

Cite this article as: Chaplow, Chris. 2014. ?andalucia.com revisited: Geographic names policy in the Domain Name System up to the mid-2000s?. Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy 2 (1): 23.1-23.14. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7790/ajtde.v2n1.23. Available from: http://telsoc.org/journal